The pandemic be damned. At a time when many galleries around the world remain closed indefinitely, one show has reorganised itself and confidently pressed on. Held in late January, the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair proved that even amid a global health crisis, the world thirsts for art, and increasingly, African art.

The first major international art fair dedicated to contemporary art from Africa and its diaspora, 1-54 was founded in London in 2013 and is staged regularly in the British capital, New York and Marrakech. But this year, with plans to exhibit in Marrakech scuppered by the pandemic, organisers quickly decided to make a Parisian debut instead — at collaborator Christie’s Avenue Matignon headquarters.

Named for the 54 countries that constitute the African continent, the platform was founded to improve the representation of African art in international exhibitions. Besides normalising the existence of African art, it has over the years become a springboard for diverse perspectives in the larger discourse on contemporary art.

Touria El Glaoui, founding director of 1-54 and daughter of Moroccan artist Hassan El Glaoui, recalls: “Contemporary arts from Africa and its diaspora have repeatedly been under- and misrepresented in art scenes in the West, but it was after supporting my father with his exhibitions that I realised how little support or opportunity there was for artists from Africa who were trying to present work internationally. It was from this that I started formulating ideas for 1-54.”

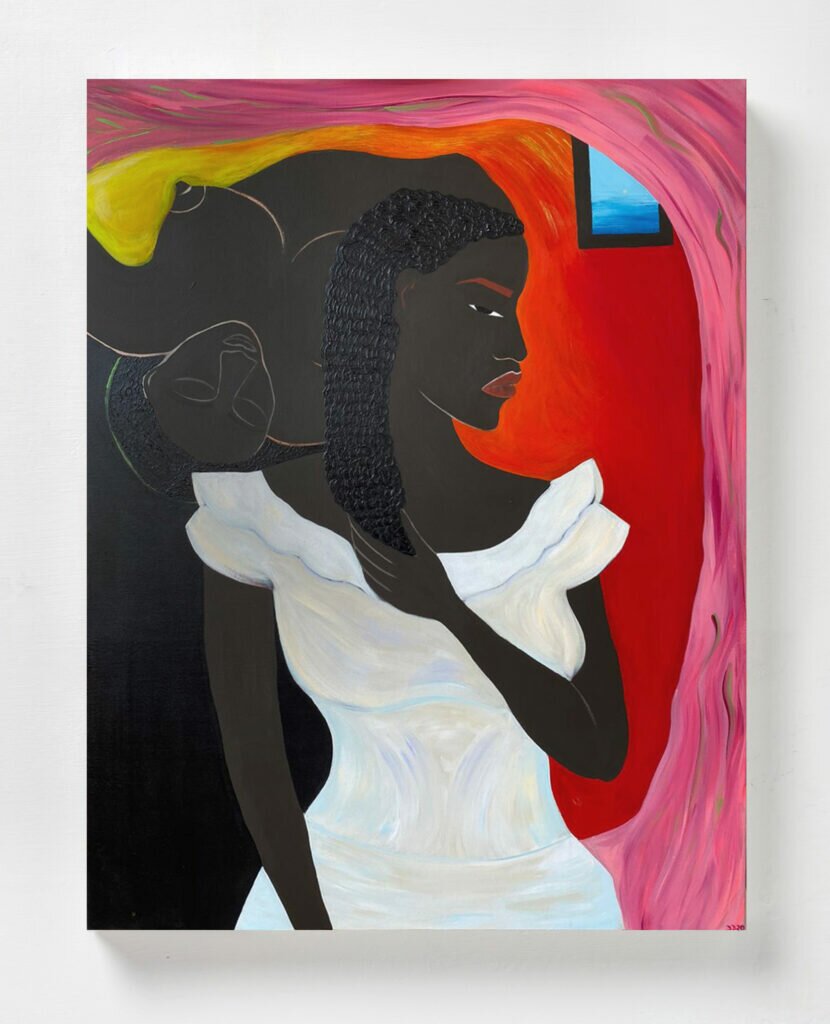

The invitation-only affair in Paris brought together 20 international galleries and the works of more than 70 artists (while complying with public health regulations). Loft Art Gallery presented photographs by Mous Lamrabat, a Moroccan-Belgian photographer who splices references from his heritage with emblems of consumerism. Luce Gallery showed pieces by New Yorker Delphine Desane, an artist born in France to Haitian parents, whose depictions of black womanhood raise awareness of the historic lack of black representation in the mainstream media.

Galerie Nathalie Obadia championed Nú Barreto from Guinea-Bissau, whose works propose a political view of the African continent, especially post decolonisation. Galerie Cécile Fakhoury exhibited Roméo Mivekannin, born in the Ivory Coast and living in Benin, who uses iconography linked to the colonial period and European art history to create canvases that transform the original narrative.

The market for contemporary African art has developed steadily over the past two decades, and collectors are responding. This is thanks in part to what may now be described as a proliferation of major exhibitions and art fairs dedicated to African art. Among them, 1-54, Documenta, the Venice Biennale, Dakar Biennale and Sharjah Biennial. Respected art galleries such as Gallery 1957, Polartics and THK Gallery have also opened in the continent, and a speculative secondary market interest in African artists is on the rise.

Gallerist Cécile Fakhoury points to Malian photographer Malick Sidibé’s Golden Lion win at the Venice Biennale in 2007 and to strong auction results by Congolese painter Chéri Samba for helping accelerate transactions and significant auction turnover advances.

“These events give the public the keys to understand these artistic scenes, leading them to become interested in them, then to buy their art and support the continuation of their creation,” she explains.

“Today, we observe that this interest is growing among international collectors and institutions, but also among collectors and important cultural decision-makers on the continent.”

Africa’s contemporary artists are achieving astounding sums at auction: Among them, Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, whose aluminium and copper wire Paths to the Okro Farm (2006) was purchased for US$1.45 million ($1.9 million) at Sotheby’s New York in 2014.

In his auction debut, a painting by emerging Ghanaian artist Amoako Boafo sold at Phillips London in February 2020 for £675,000 ($1.25 million), more than 10 times its high estimate. An overnight art market darling, his spectacular rise is partly due to the patronage of Miami-based collecting family, the Rubells, who invited him to become the first artist-in-residence at their new private museum, which opened to coincide with Art Basel in Miami Beach in 2019.

The work of certain individuals has been instrumental. Personalities like Cameroonian writer and art critic Simon Djami, influential Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor, who challenged EuroAmerican-centric perspectives within the contemporary art world, and French art historian Jean-Hubert Martin with his exhibition Magiciens de la Terre at Centre Pompidou in 1989, have boosted knowledge of the African scene.

At the same time, the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, DC, is today home to an exceptional and ever-growing collection of African art. Jean Pigozzi, the largest-known private collector of contemporary African art, donated 45 sub-Saharan artworks by the likes of Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Seydou Keïta, Romuald Hazoumé, Moké and Chéri Samba to MoMA in New York in 2019.

“The African continent has become an exciting art scene with highly invested artists who are now exhibited worldwide,” notes gallerist Nathalie Obadia.

“What has changed is that artists have studied in art schools in African countries, and although they have studied in art schools abroad, they choose to work in Africa or spend a significant part of their time there. More and more galleries are doing international promotional work, more and more collectors from the African continent are active and numerous, and museums and private foundations are also emerging.”

Everyone is trying to get in the game, discover new artists and make sure they are part of the discussion, while at the same time fixing the omissions of history by amplifying African voices.

Over the last 10 years, prestigious international galleries have integrated African-American, African-British or African artists, sending a strong signal of confidence. David Zwirner collaborates notably with Kerry James Marshall, Njideka Akunyili Crosby and Noah Davis, while Nathaniel Mary Quinn has been with Gagosian since 2019.

Hauser & Wirth represents a dozen artists from the African diaspora, including Amy Sherald, Lorna Simpson, Mark Bradford, Henry Taylor and Simone Leigh. White Cube promotes the work of Ibrahim Mahama and Theaster Gates, Almine Rech supports Genesis Tramaine and Madelynn Green, while Galerie Templon accompanies Kehinde Wiley and Omar Ba.

Many buyers are happy to take a chance on the development of artists who have just joined a large gallery, even when their reputations have yet to be established. The link between signing a contract with a major gallery and a boom in prices can be immediate. Nigerian-born Toyin Ojih Odutola’s From a Place of Goodness (2017-2018) fetched US$62,500 versus a low estimate of US$10,000 at Sotheby’s in 2018, months after she inked a contract with Stephen Friedman Gallery. Her works have now surpassed the US$500,000 threshold.

According to Galerie Cécile Fakhoury, which sells works ranging from €2,000 ($3,200) to €5,000 by its younger artists and up to €150,000 for its veteran talents, the prices of all its artists have increased over the past five years; sometimes tenfold, as was the case with Senegalese painter Kassou Seydou. Still, Fakhoury observes: “Overall, I would say that African artists are still undervalued. There is a fantastic margin for progression.”

Many artists’ works are often focused on themes of identity, race, culture and politics, but Obadia warns that “there are profiles that are very much in demand from collectors and museums — narrative figurative painting — where the risk is to lock young artists into this type of production in order to sell quickly and a lot, and other directions like abstraction and conceptual installation are neglected”.

The rise of contemporary African Art is the result of decades of hard work, adds 1-54’s El Glaoui.

“It’s been a slow change. Prices have risen but they are still relatively low in comparison to the prices for works made by Western artists and sold in Western spaces. But this is encouraging as the increases we are seeing are sustainable for the market and allow for younger and less financially wealthy collectors to enter the market.”

“Likewise, major collectors come from around the world and across the continent. This diversity is healthy for Africa’s contemporary art scenes and the markets, as there is no reliance on or pressure by a single demographic, therefore discouraging purchasing trends and targeted price brackets.”

The story of contemporary African art may still be in the process of being written, but with fairs like 1-54 helping to shape a compelling new narrative, it is resonating with a global audience and coming into its own.

This story first appeared in the March 2021 issue of A Magazine.