The Covid-19 crisis has highlighted — and intensified — our dependence on digital technologies, with social- distancing rules forcing people to take their work, education and personal relationships fully online. But as governments enact sweeping emergency measures, including to combat disinformation and trace the contacts of infected people, the crisis has also created a serious threat to digital freedom.

For nearly a decade, digital freedom has been declining globally, largely owing to the proliferation of mass surveillance and the manipulation of political discourse. The pandemic could accelerate this process as it gives governments a compelling justification for forcing companies within their jurisdiction to control content and hand over data.

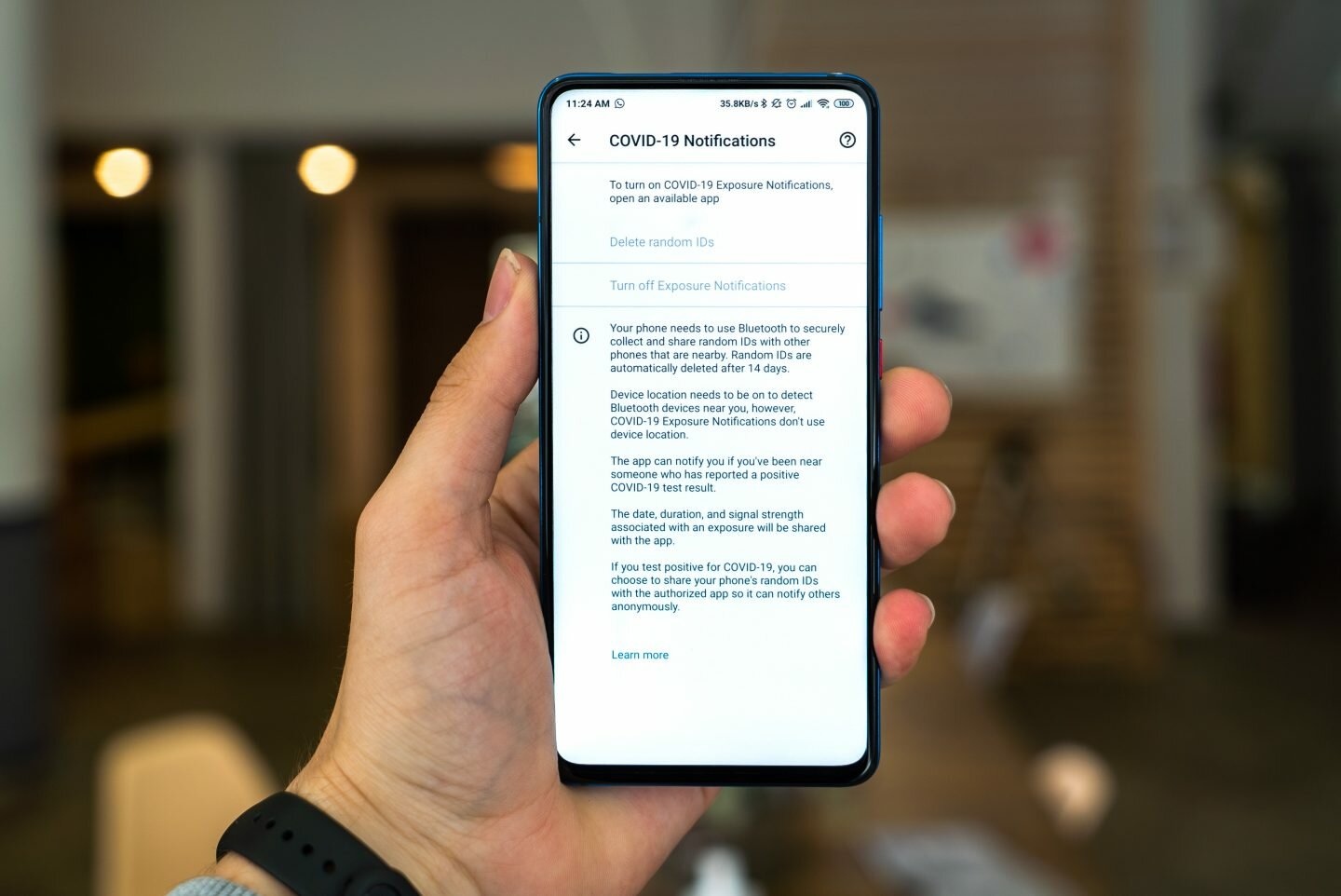

To be sure, tech companies have a role to play in ensuring that people receive accurate information, especially during the current “infodemic”. And widespread contact tracing, such as through Bluetooth-enabled apps, may help countries reopen their economies more safely — a possibility that even some staunch civil libertarians recognise.

But controlling content and handing user data over to governments is a slippery slope to censorship and surveillance, including of journalists and human rights defenders. These are grave violations of civil liberties, and tech companies should be wary of blindly acceding to government demands that might facilitate them.

Yet, pushing back against such demands is not easy, and disputes between the private and public sectors over data sharing have often been contentious. That’s why, in 2008, the Global Network Initiative (GNI), whose board I chair, developed a set of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Privacy. Grounded in international law and overseen by GNI, these principles aim to guide companies on how to handle requests from governments to censor content, restrict access to communications services or share user data.

Every two years, companies participating in GNI are independently assessed on their progress in implementing these principles. The latest assessments of 11 tech and telecom companies (conducted before the pandemic) provide valuable lessons for companies attempting to navigate new pressures, well-intended or otherwise, from governments.

The first lesson is that Benjamin Franklin’s dictum that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is as true for human rights as it is for human health (or fire safety, which is what Franklin had in mind). While nobody can predict the future, companies can employ due diligence to identify censorship and surveillance risks and to avert or mitigate them. Nokia’s process for evaluating equipment sales and Microsoft’s inclusion of lawyers in its business groups to support it on protecting users’ rights exemplify this approach.

Second, increasing transparency is always worthwhile, no matter how challenging the circumstances. For example, gag orders often prohibit companies from disclosing information about national security requests. But GNI’s assessments show that companies can push back, such as by challenging such orders in court, fighting laws that enable governments to obscure their surveillance activities and increasing transparency in their own reporting.

The third lesson is that companies can do more to keep communication networks accessible. Restricting such networks threatens emergency services, limits access to vital public health information and blocks the provision of life-saving telemedicine, making it a particularly dangerous policy during a pandemic. Yet, government-ordered network disruptions are becoming increasingly common.

Six case studies, covering seven countries, show that such orders are often facilitated by missing or inadequate governing legislation. Moreover, companies may feel they have little choice but to comply, whether due to a lack of recourse to legal means or credible security risks to employees.

But companies have managed to resist verbal shutdown orders, pushing governments to issue signed and dated written orders that cite the relevant legal provisions. Some have achieved this by requiring that such orders be escalated to senior management; some have also engaged directly with the authorities to convince them to keep disruptions narrow, affecting a particular site or service, rather than the entire network.

A fourth lesson is that the best defence against undue government pressure is robust policies and procedures. Governments often have compelling reasons — a pandemic, terrorism, child exploitation and cybercrime, to name a few — to pressure companies to hand over data. Companies need a clear and reliable system for dealing with such requests, anchored in international human rights law, to ensure that efforts to address security risks do not enable the suppression of freedom of expression and the violation of users’ privacy. The GNI assessments also provide insights into how companies can adapt their responses to different jurisdictions.

As governments worldwide push technology companies to put their data to use in the fight against Covid-19, oversight and accountability are more important than ever. Instead of conceding that an effective pandemic response requires infringing freedom of expression and privacy rights, companies must recognise that civil liberties are critical enablers of global health and act accordingly — even when governments don’t.

Mark Stephens is chair of the Global Network Initiative, a multi- stakeholder voice whose mission is to protect and advance freedom of expression and privacy rights in the information and communications technology sector.

Text copyright Project Syndicate, 2020.