Late in 2017, when auction house Christie’s banged the gavel on the astounding top bid of US$450 million on Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, it set the record for the most expensive painting to be sold at auction. Nothing came close to outstripping that transaction — that is, until early March this year when the auctioneer concluded the sale of Everydays: The First 5000 Days at US$69.3 million.

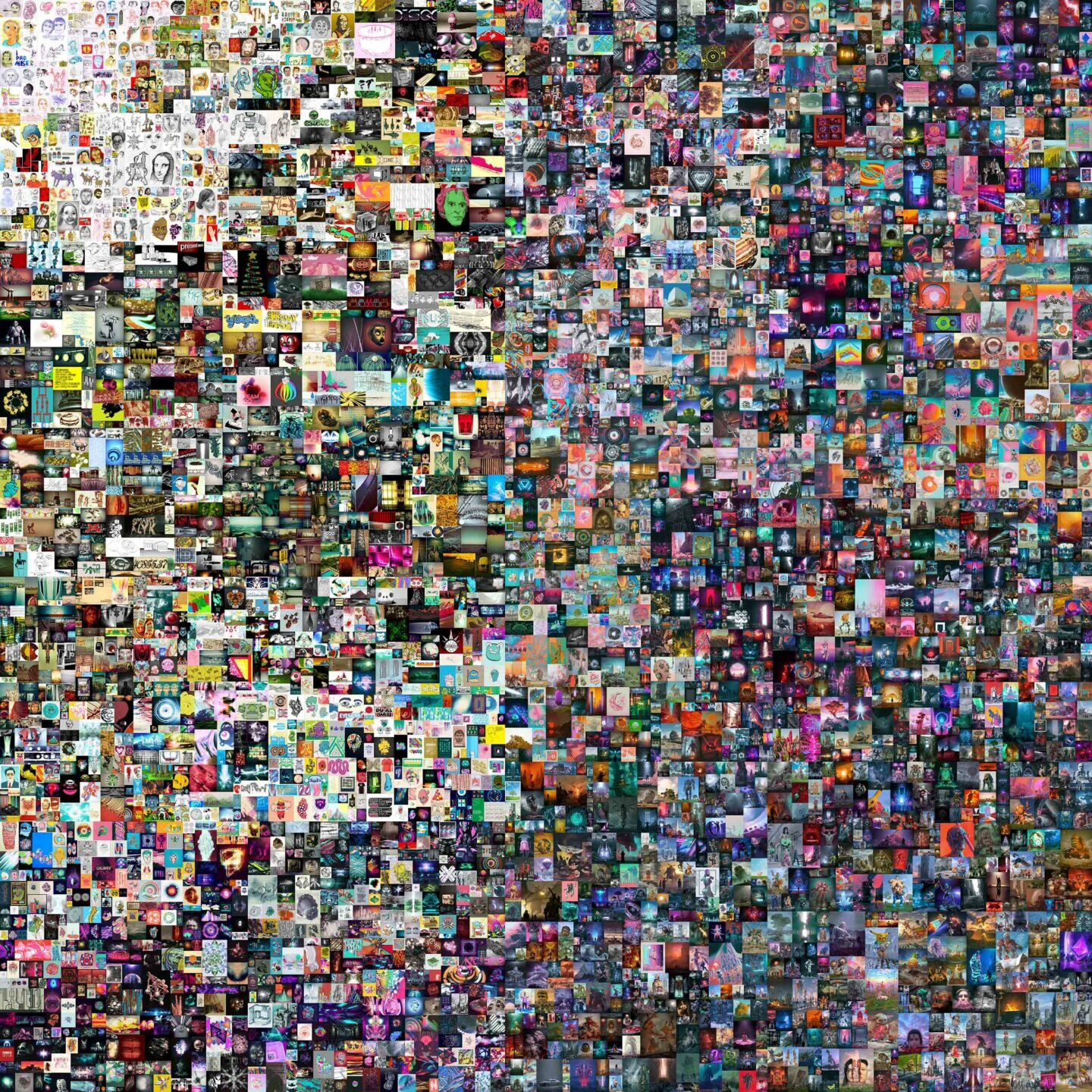

It’s no Mundi-scale price tag, but then again, it’s no Mundi: The work was created by digital artist Beeple and is represented by a non-fungible token (NFT). With it, Christie’s achieved the third-highest auction price for a living artist and marked its first sale of a purely digital work in cryptocurrency.

And at it, the art world scoffed. “JPG File Sells for $69 Million,” The New York Times quipped. “NFTs are Creating the Opposite of Everything They’re Meant to Fix,” went ARTNews. Meanwhile, critics rallied to anatomise the work, the sale, and the NFT market.

For better or worse, such disruption was why the auction’s highest bidders, Metakovan and Twobadour of the Singapore-based crypto fund Metapurse, threw their Ethereum behind the work. “One of the bigger reasons why we went for Beeple was to divert the attention of people to the space,” Twobadour (aka Anand Venkateswaran) tells me. “It’s sort of a clean slate and in a sense, it decentralises culture because there is no totem pole in the crypto art space.”

NFTs, though, have been around long before the mainstream was paying attention. And what even are NFTs? They’re unique digital tokens that can represent anything from artworks to sneakers, and that live on blockchain technology, which hosts the systems where NFTs can be securely bought and sold in cryptocurrency. Minting an NFT of, say, a Gif you just created certifies you as the author of the work; a sale or resale of your token earns you a cut of royalties, though each transaction confers ownership of the NFT, not the work’s copyright or license.

Since the emergence of blockchain networks such as Ethereum and Bitcoin in the mid-2010s, digital or crypto art has taken root, attracting artists and collectors drawn to the technology’s promise to democratise and decentralise the art economy. Platforms from OpenSea to Foundation have popped up to facilitate sales in a manner that’s swift, secure, and transparent (transaction records can be accessed and viewed by all), and entire communities, encompassing art lovers, gallerists, and event organisers, have rallied in appreciation and support of crypto creators. Late last year, the pseudonymous Pak became the first crypto artist to make US$1 million off their Ethereum-based creations.

Image: Chris Torres

Christie’s Beeple sale, however, has changed things, inflaming an NFT mania that’s seen tweets, one Kings of Leon album, a LeBron James highlight reel, a Pizza Hut pizza, and the Nyan Cat meme land in the crypto marketplace. In February, Vincent, an investment search engine, reported a 44 percent surge in interest in NFTs, just as the National Basketball Association’s Top Shot blockchain platform raked in some US$53 million in a week. Meanwhile, Pak’s works are headed to auction at Sotheby’s. But amid the rush, it’s worth nothing, as Twobadour does, “The current explosion that you see right now is not the real explosion of NFTs, but around the acquisition of NFTs.”

Still, all that is bound to unsettle a crypto art space that’s long thrived in a niche, without gatekeepers, and outside the media spotlight. Speaking to Dazed, digital artist Aaron Jablonski reflected, “This whole space is in a craze state right now,” with film director Eva Papamargariti adding, “I think it is quite useful to take a step back and watch the situation from afar sometimes, examine it and approach it with a kind of thoughtfulness instead of an ongoing relentless ecstasy.”

There’s not much hope there. Rather, the attention of the media and art establishment is fast turning sharp, as commentators take a knife to the ecological cost and asset value of NFTs. Not that all of it is unfounded. A single Ethereum transaction consumes enough energy to power an American household for two days and Bitcoin has been found to devour more electricity than Argentina. Though some NFT players have taken to carbon offsetting and Ethereum has announced plans to reduce its energy consumption, every NFT minted right now (and you had better believe there are a lot of them) is contributing to the ongoing climate crisis.

It doesn’t help matters that investors and grifters alike have surfaced, rushing in to cash out. As investors take to snapping up NFTs and chancers commence minting artworks they don’t even own the rights to, you can practically feel the form of a speculative bubble taking shape. And we know what happens with those — see: tulips, railways, dot-coms, and more recently, 2017’s rash of initial coin offerings. As Jane Leung, the chief investment officer at SVB Private Bank, told The New York Times of the NFT mania, “Most people are cheering, but at the same time, shaking their heads and going, when is the bust coming?”

Image: OpenSea

The skepticism surrounding NFT purchases and ownership — What is it you actually own? Why fork out that much for an intangible thing? — has also been trained on Beeple himself. Specifically, his highly priced work, collaging 5,000 images he made every day over some 13 years, which artnet analysed to discover his earlier racist and sexist pieces that hardly warrant critical praise, much less a hefty price tag. Is it mere provocation, or the product of a blinkered mind?

The same could surely be asked about physical works from Jeff Koons’ Made In Heaven series to Richard Prince’s New Portraits. None of them are excusable and yet, in an art world that has glossed over Picasso’s painted misogyny and shelled out for Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian (you know, the banana duct-taped to a wall), there they are.

Our pandemic reality — which has seen events such as the Complexland digital festival, RTFKT’s “virtual sneakers”, and Cyberpunk 2077’s mainstream crossover — may have eased its arrival into mass consciousness, but the long-bubbling crypto ecosystem will disrupt and challenge as any newcomer to a scene will do. Remember the entry of street art or Young British Artists onto the art market? When the growing pains are past, NFTs, likewise, are in it for the long haul. Today’s NFT-buying fever will break, or as Beeple puts it, “This stuff will absolutely go to zero,” but there’s every chance the crypto space will outlast the current moment (just as it’s preceded it) to keep championing, broadening, and bettering its own alternative economy.

Metapurse already has its eye on that horizon, with plans for a “virtual monument” to Beeple’s name-making artwork that will exist across virtual worlds (the next NFT frontier!) like Decentraland and Cryptovoxels. The point, says Twobadour, is for visitors to “experience NFTs as they’ve been originally intended.” He adds, “We believe that is where the ecosystem is headed and we want to be catalysts in that movement.” And so the paradigm shifts. Salvator Mundi, take a seat.