Singapore prides itself on being among the world’s greenest cities. But to visual artist Marvin Tang, there is more to the story of its sculpted greenery and “A City in a Garden” slogan. Through his work, he attempts to dissect its structural, cultural and historical narratives and explore the idea of collective identities.

In his latest research project The Colony (2018 – ongoing), Tang — currently artist-in-residence at the NTU Centre for Contemporary Art Singapore — examines the role and impact of botanical institutions established during the colonial era.

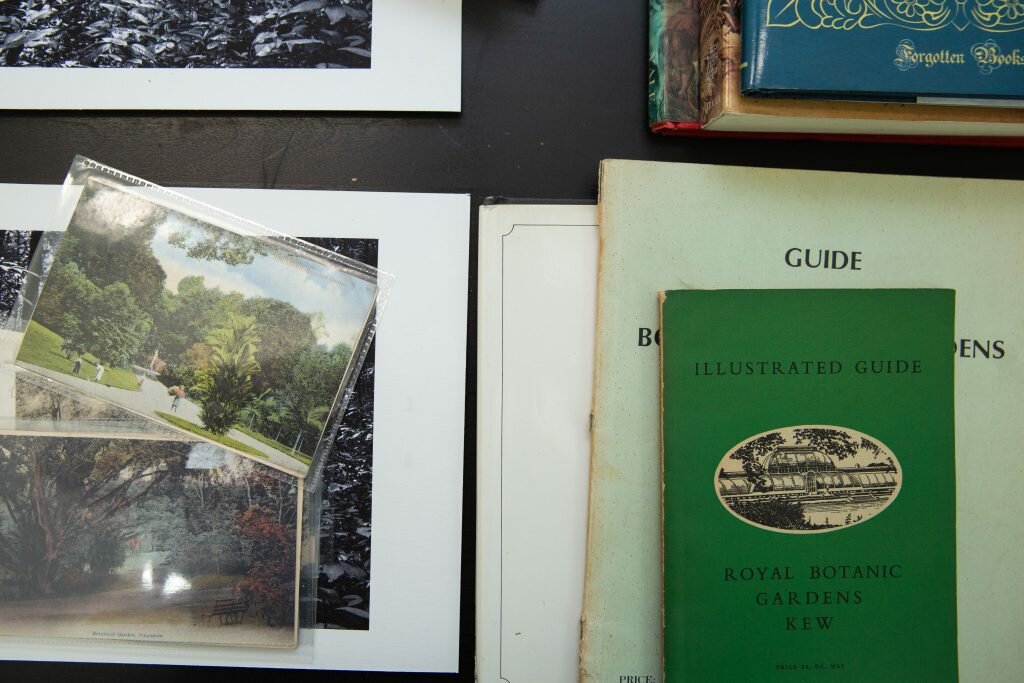

“Singapore’s Garden City story doesn’t just begin with founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew but dates as far back as our colonial history,” explains Tang, from his residency studio at Gillman Barracks — an airy space filled with mini LED-lighted terrariums, stacks of research papers, maps and illustrations of plant species tacked on walls. An array of latex cubes, representing an average yield of a Hevea brasiliensis (rubber tree) at its prime, lines his desk.

Tang’s project focuses on the movement of seeds, plants, and people at a time when the British established its overseas colonies between the 16th and 19th centuries. The British empire, at its height, was the world’s largest, with conquests spanning North America, Australia, Africa, and Asia.

According to Tang, the colonial power “saw the world as its plantation” and envisioned a planetary garden where it would bring valuable plants on expeditions to far-flung corners of the world for crop cultivation.

Singapore was regarded as a ripe testing ground — a place to cultivate rubber seeds from Brazil and nutmeg from Indonesia’s Spice Islands, as well as plant Senegal Mahogany trees from Africa, which are still among the biggest evergreens that line our parks and roads.

Tang’s research was partially inspired by his fascination with the Wardian case — invented by British physician and fern enthusiast Dr Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward in the 1830s — a forerunner to the modern terrarium. A protective enclosure with glass windows, it allowed plants to endure long sea journeys and played a part in dramatically reshaping global politics and trade.

But it was while studying for his Masters in Photography, at the University of the Arts London, that the idea for The Colony took root. It had hit him that colonial systems weren’t just historical legacies that had been put to bed. “I realised how unaware I was of their butterfly effect and how we continue to live with remnants of colonisation every day,” he shares.

For instance, it was the implications of global plant migration and the need to sustain booming plantation economies in the colonial era that led to massive labour migrations — a key force in shaping Singapore’s entrepot port status as well as multicultural identity, with British officials and Chinese and Indian labourers flocking to Singapore for work and opportunity.

Nature also featured prominently in Tang’s previous works, which sought to establish a new understanding of the environment here.

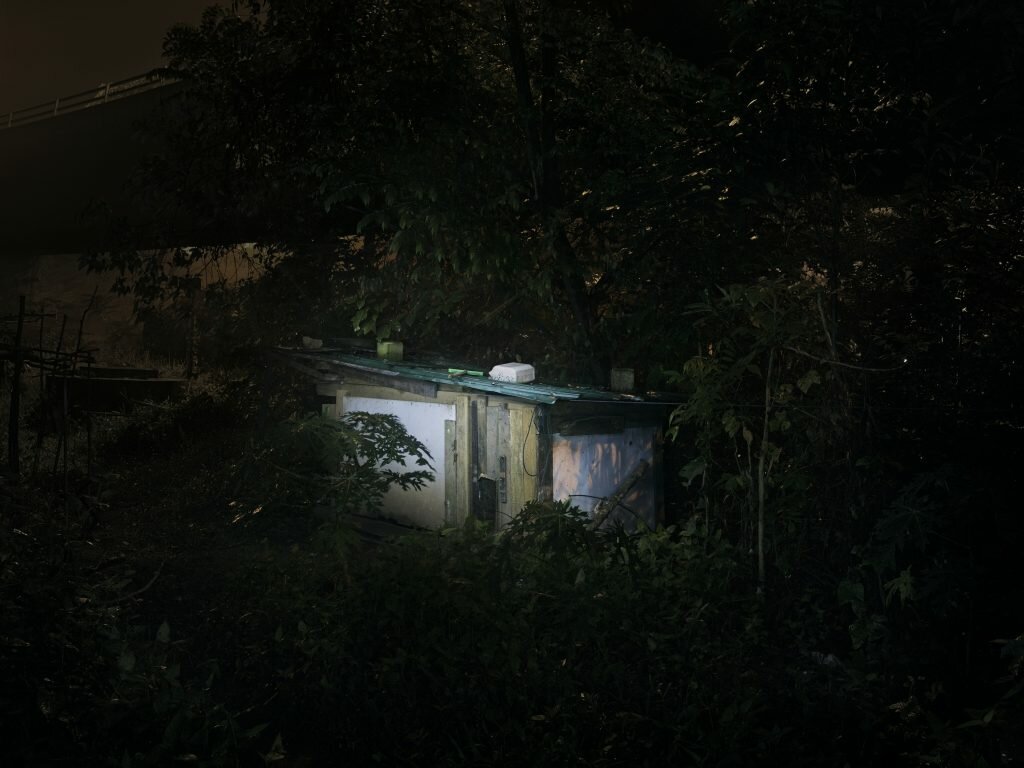

He first began to investigate the citystate’s complex relationship with its garden identity in Stateland (2015), which depicts plots of gardens and plantations formed secretly within the state-owned forested grounds in Singapore. His forays into the forests in Thomson Road and Choa Chu Kang delivered unexpected discoveries: a chilli plantation half the size of a football field, flourishing plots of eggplant and okra, even a bag of used condoms thought to be from a forest brothel.

From talking to gardeners, Tang learnt that the plots were grown by nearby residents who were mostly retirees with a longing to relive their kampung days. In rapidly urbanising Singapore, cultivation on state land is one way for citizens to reclaim land for themselves and make it their own. “It’s very telling of how space is a huge want for people, especially in a concrete jungle like Singapore,” he says.

Likewise, in Invaders (2014), Tang imagines a world overtaken by lush nature, as inspired by Alan Weisman’s book The World Without Us. In 2018, he presented The Mountain Survey (2018) at Alliance Française Singapore, which depicts various mountainous landscapes and nature reserves in Singapore. Once vital during the building boom in the 1970s to 1980s, these “mountainous” former granite quarries are now spaces of tranquility.

Most recently, The Colony Archive (2019 – present) — a subset of the wider The Colony project — was presented at the group exhibition The Seeds We Sow, which opened in April at the Mizuma Gallery. Featuring the works of four local artists, the exhibition centres on themes such as the tension between human intervention and the natural environment.

“We align ourselves so much with this ‘city in a garden’ narrative, but in reality it’s difficult to define what exactly nature is, especially when so much of it is just secondary forests and when more and more gardens are being built by the authorities now,” Tang shares.

“I sometimes wonder if our idea of nature will be shaped by NParks.”

Still, Tang is quick to dismiss notions of his work being read as anti-establishment. “All systems of power need to be critiqued. But at the same time, it is these decisions that make up our environmental and natural history,” he says.

Beyond seeing nature spots as just tourism magnets, Tang feels that citizens can understand their collective narrative when they know more about the plants in Singapore, their origins and influence. Only then can they truly have ownership over it.

“It goes beyond romanticising the idea of us living on a tropical island. As citizens, we need to be convinced of this identity, to consume it in our own way, and to allow for it to develop in our own sensibility,” he says.