On 29 March in New York City, a 65-year-old Filipino woman was physically assaulted while on her way to church. Earlier, in February, a Korean-American veteran was attacked in Los Angeles; in January, in Portland, Oregon, an Asian woman and her son were assailed with kicks and racial slurs while riding a bus. On 16 March, a white man walked into three spas in Atlanta, Georgia, and opened fire, killing eight people, six of whom were Asian. According to a survivor, the shooter had declared: “I’m going to kill all Asians.”

These make up just a handful of anti-Asian incidents that have occurred so far in the US this year. The media may be swarming about the issue now, just as IG accounts are jumping in with calls to #StopAsianHate, but the anti-Asian tide has been roiling online and on the streets since the onset of Covid-19 in 2020. Fuelled by the fear and frustration engendered by the virus, and an ex-President’s thoughtless racialising of the pandemic, the number and fatality of anti-Asian crimes have grown to shattering proportions. As Grace Meng, democratic representative of New York, tweeted: “We’ve gone from being invisible to being seen as sub-human.”

Then again, anti-Asian sentiment has deeper roots in the United States, a country that has racism built into its very structures. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the exhibition at the 1904 World’s Fair which depicted native Filipinos as “savages”, the 1942 Japanese concentration camps, the hate visited on Muslims post-September 11 — these xenophobic signposts have actively othered the Asian community for simply being who they are. But even in the absence of a pandemic or terrorist attack, anti-Asian animus can easily be seen on the most American landscape of all: the Hollywood film.

Image: Eugene Robert Richee/Paramount Pictures

Depictions of East Asians on Western film can be traced as far back as the dawn of the 20th century, though none make for a pretty picture. For one, as is Hollywood’s wont, Asians have been portrayed by Caucasian actors in unfortunate “yellow face” makeup — as in 1918’s The Forbidden City and 1937’s The Good Earth. And even when played by Asian actors, Asian characters were diminished, fetishised and caricatured in line with white biases.

Take Anna May Wong, now remembered as Hollywood’s first legit Chinese-American star. Wong had slim pickings when it came to on-screen parts, playing either the demure, long-suffering “Lotus Flower” (see 1922’s The Toll of The Sea in which she played a character named Lotus Flower) or the scheming temptress in films like 1931’s Daughter of the Dragon. Typical of the time, Wong’s roles were intended to represent the allure and mystery of the Orient as much as the existential fear roused by an alien culture.

“Anna May Wong symbolises the eternal paradox of her ancient race,” as one irony-free fan magazine put it then. “She reminds us of cruel and intricate intrigues and, at the same time, of crooned Chinese lullabies.”

One more thing: Wong also holds the questionable world record for the most on-screen deaths, often by suicide. For reasons only known to white screenwriters, suicide was viewed as an Asian trait and thus, a fitting end for Asian characters. Don’t even try to make sense of it. As Eugene Franklin Wong wrote in On Visual Media Racism: “The image of both Chinese and Japanese in the media depended more on political factors among the Caucasian population of the United States than upon the characteristic behaviour or attitudes of either immigrant group.”

Subsequent decades’ worth of motion pictures have done little to correct such narrow depictions. When not underrepresented, the Asian identity has been misleadingly portrayed as monolithic, cobbled together with random elements from various East Asian cultures to make up a nonsensical whole. On screen, Asians speak heavily accented English, are really good at maths or martial arts, and are either hyper-sexualised or desexualised. If you think the likes of Mr Yunioshi of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and Long Duk Dong of Sixteen Candles are safely ensconced in Hollywood’s past, don’t forget Trang Pak of Mean Girls or Mr Chow of The Hangover films, who have turned up as recently as this century.

And do nuanced filmic depictions of Asians even matter? Of course they do. Like a President’s rhetoric, films exist in the public sphere and bear some manner of social responsibility. On screen and IRL, even the most casual stereotype is dehumanising.

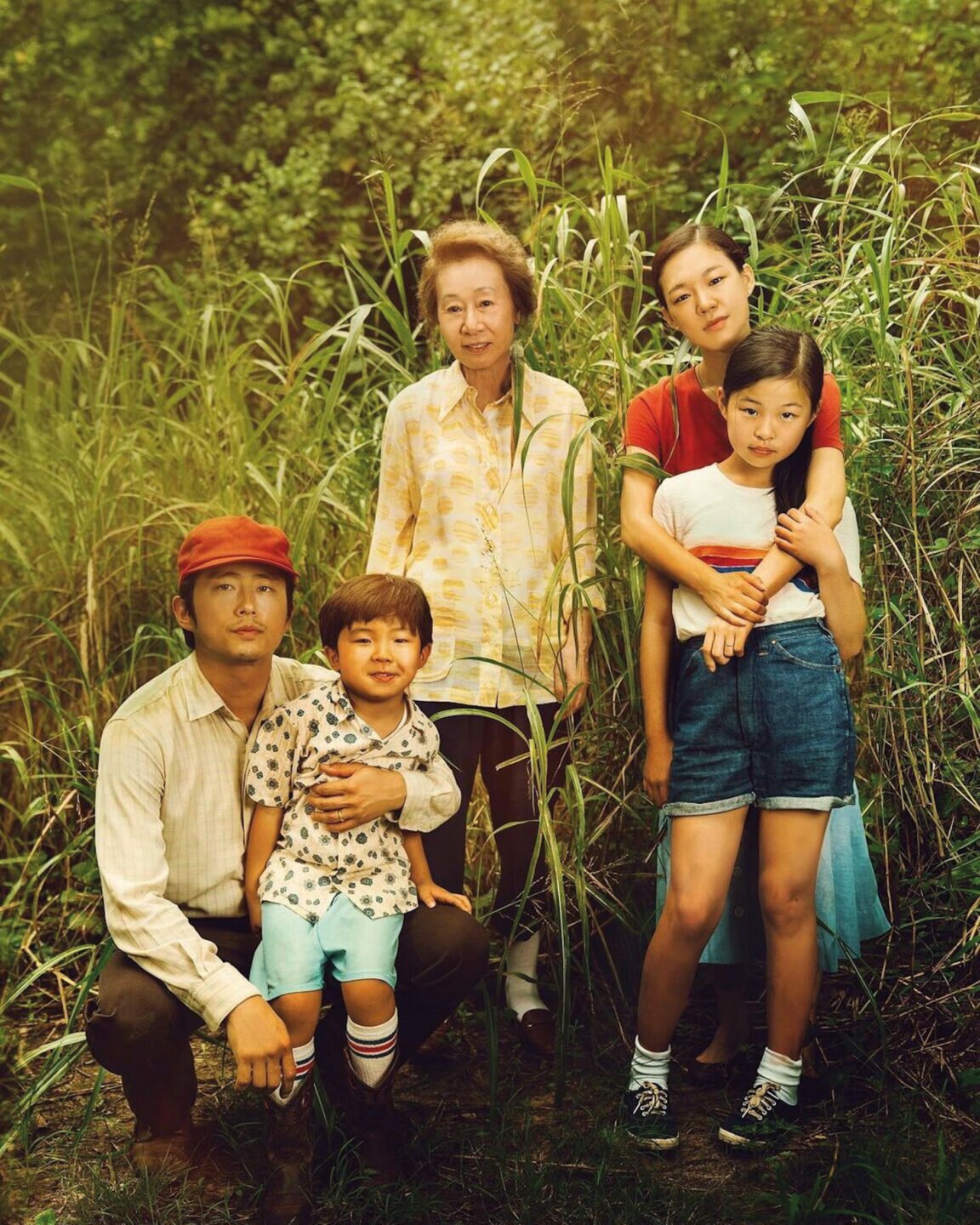

The past few years, though, have brought a heartening shift in on-screen Asian representation. TV series and films from Fresh Off The Boat to To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before have brought authenticity and added visibility to Asian cinematic depictions — buttressing an increasingly vocal Asian-American community that’s exploding long-held perceptions of Asians as the “model minority”. The blockbuster success of Crazy Rich Asians, The Farewell and Minari further signal that an appetite exists for Asian-centric stories.

Crucially, even as they add dimensions to the Asian-American experience, these productions have refused to particularise that experience. In other words, they’ve endeavoured to make Asian narratives universal. Billi in The Farewell could be any one of us bidding a final goodbye to our grandmother, just as Fresh Off The Boat’s Eddie Huang could be any and every kid discovering his calling. Jenny Han, author of To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, on which the 2018 film was based, told Teen Vogue of her protagonist: “It was important that [her Korean-American heritage] be a part of her identity, but not the whole of her identity.”

The industry looks to be just waking up to Asian representation, but it can’t claim to be totally unschooled on the subject. In 1993, the critical and commercial enthusiasm that greeted the release of The Joy Luck Club, which boasted a largely Asian cast, kindled optimism for the future of Asian-Americans in the space. Hollywood, however, quite simply did not follow up: in 2018, director Wayne Wang characterised his later efforts to cast more Asian actors in his pictures as “a fight that I couldn’t win”. Yet, the film’s legacy stands (it’s preserved by the Library of Congress in its National Film Registry) — as, against all odds, does the career of one of its lead actors, Ming-Na Wen.

Following The Joy Luck Club, Wen would ride Hollywood’s occasional interest in diverse casting, playing Asian characters like Mulan and Chun-Li in Street Fighter, while pursuing “roles that weren’t specifically Asian to begin with”, according to her. Case in point: the part of Deb Chen in the long-running TV series ER, which was renamed once Wen was cast. Today, she’s the only Chinese-American actor to have starred in three major franchises: in Disney’s Mulan, Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D and Star Wars’ The Mandalorian.

In these roles, she’s no wilting Lotus Flower, shady vixen or nerdy maths whiz, but simply a character uniquely defined by her motivations and not her ethnicity.

“That, for me, is the biggest way to influence anyone,” Wen told The Straits Times. “They’re seeing the character, they’re falling in love with the character, and oh, he or she just happens to be Asian.”

Better yet, audiences, Asian or not, might just see themselves too.