With words like “inspiration”, “reference” and “homage” becoming standard garnishes on press releases while serving as invisibility cloaks for designers, watchdogs for the fashion industry are more crucial now than ever.

Critics are on the demise—few are in the position to call out crap, no thanks to advertiser intervention, readership decline and rigid publicists and stylists. Does this generation have a Cathy Horyn or Robin Givhan? It’s a deafening “no”, as evidenced by the army of paid millennial fashion influencers at presentations, recommending products they don’t care for and posting mediocre #ootds.

We can blame social media for such an unfortunate state, but we must give credit where it’s due: power is now in the clicks of a collective on the Internet. Someone is watching over the brands, designers, magazines and tastemakers—not as a single individual but as an entity of many contributors.

Finally, someone’s on our side. Satirical fashion Instagram accounts @stressedstylist and @fashionassistants speak for themselves. The beauty industry has @esteelaundry, advertising @dankartdirectormemes, and graphic design @makethelogobigger.

-

@diet_prada -

@diet_prada

The biggest among them (arguably) is @diet_prada. Founded by Lindsey Schuyler and Tony Liu in 2014, it’s been described by former Lanvin designer Alber Elbaz as the account “every designer in the world is following”. Although Diet Prada (DP) skyrocketed to prominence by anonymously calling out designers ripping off others, its posts went on to cover topics such as designer scandals, buyouts, reviews, misogyny, model mistreatment and racism.

DP was responsible for the takedown of Dolce & Gabbana’s Shanghai show, after it uploaded racist messages by designer Stefano Gabbana. Not one to hold back on criticism, it even lashed out at Alessandro Michele for cultural appropriation during a paid live stream of Gucci’s fashion show. Actions like this have cost the crème de la crème of designers millions of dollars. Who knew a troll account would become fashion’s most ruthless and influential vigilante?

But when you’re constantly calling people out, things can get ugly. DP got itself embroiled in wars with countless influencers, including Olivia Culpo, Chiara Ferragni and Dani Austin. The worst occurred with Arielle Charnas, when she produced headbands nearly identical to Prada’s trending Spring 2019 collection. The Dieters didn’t stop at attacking Charnas for plagiarism, they even threw jabs about her baby girl. “You deserve [your] [baby] thrown under a bus,” one comment went.

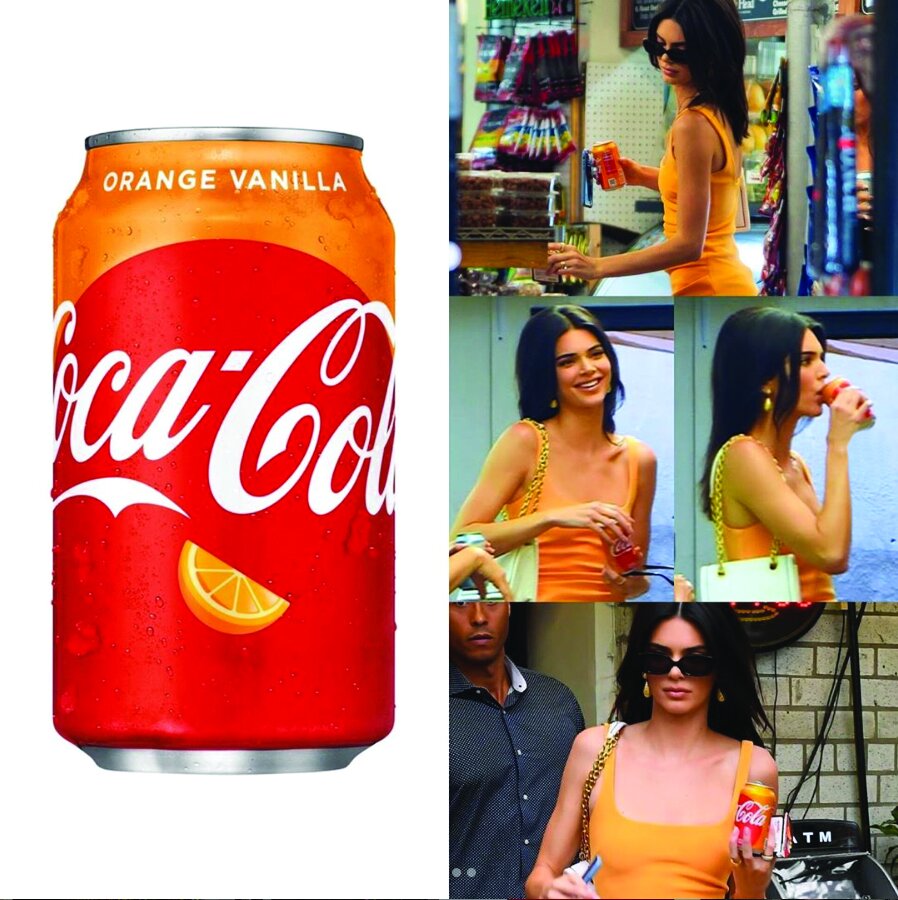

DP’s ability to garner a loyal following of informed fashionistas means it can also summon a lynch mob. A post can lead to a wanted poster or cancellation. Its tongue-in-cheek delivery can be clever and entertaining, but DP has also furthered itself as an echo chamber for sartorial snobs. (Given that it’s based in New York, it reads much like Gossip Girl.) You can list the usual targets, which include Philipp Plein, Virgil Abloh, the Kardashian and Jenner sisters, Maria Grazia Chiuri, Hedi Slimane, Jonathan Anderson and Vogue US. Sometimes, it borders dangerously close to bullying.

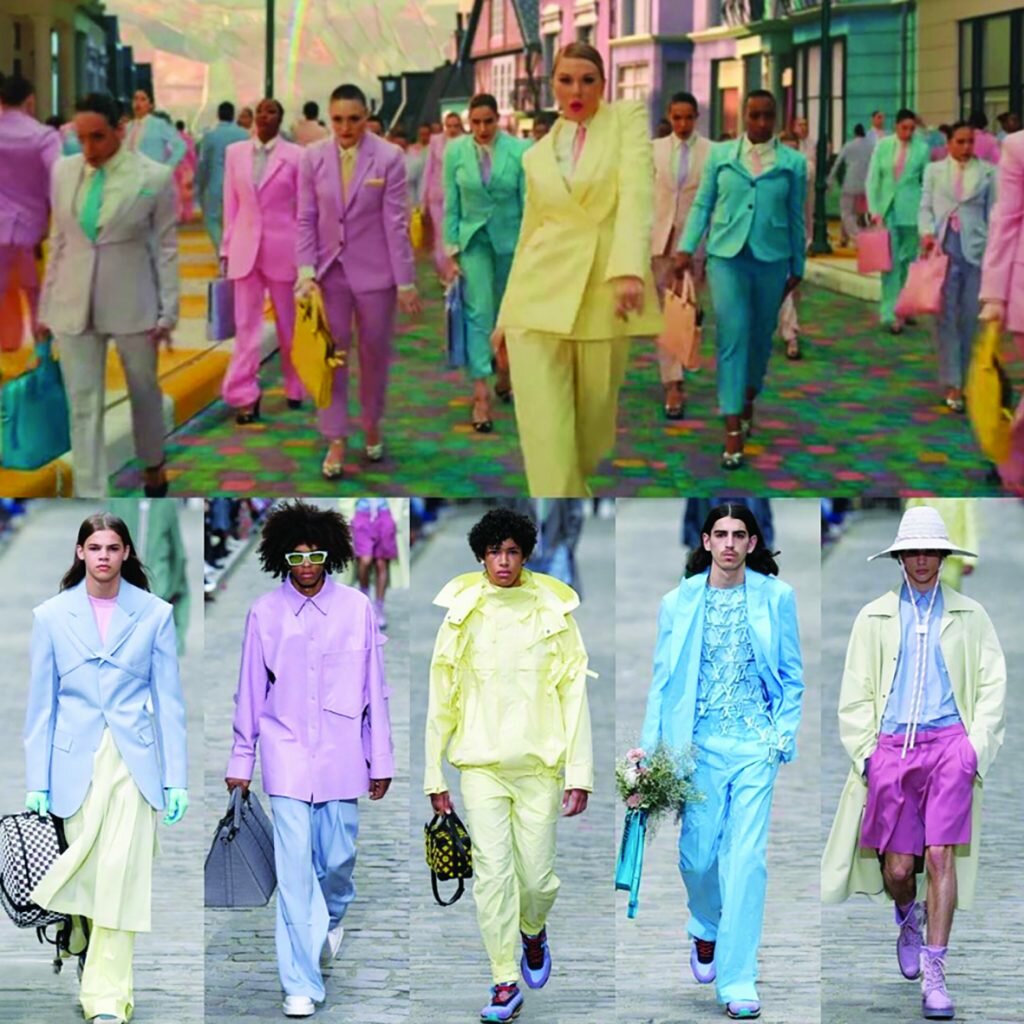

Sure, most of DP’s comparisons have been spot on, but plenty are on the verge of delusional. Aside from pitting Reem Acra against Gucci, Mugler against Louis Vuitton, and Givenchy against Maison Margiela at Resort 2018, it’s also accused Paco Rabanne creative director Julien Dossena of knocking off Yohji Yamamoto—who was originally inspired by Paco Rabanne.

Its methodology of determining intentional (or not) design similarity is inconsistent and raises questions; by deliberately singling out similarities in very different products, it stirs up shit rather than actually “protecting” designers. Indeed, DP has gone beyond calling out “ppl knocking each other off lol”.

People should be held accountable for their mistakes. But the danger here is that we’ve relinquished the power to speak and think for ourselves. DP’s influence doesn’t equip regular folks with sufficient and proper understanding of how fashion works now. That honour belongs to @thefashionlaw, which shares information on law, statistics and sources for further reading. The account can come across as boring but it has shored up credibility by offering genuine knowledge.

You see, barriers to entry for fashion are extremely low—many designers of the moment never went to fashion design school (yes, that means you, Virgil Abloh). Many players possess capital, access and resources but not the time or awareness that they should invest in product development. They work according to an unrealistic timeline of preparation of, say, two months, before launching a brand. What we get eventually are sub-par brands producing the same T-shirt, and counterfeiting designs off the runway at ridiculous and unsustainable prices. And since a product life cycle can only last so long, such modus operandi is accepted as making financial sense.

Although this is now the reality, it should never be considered justification for the toxic cycles in fashion. We appreciate DP for scaring away exploiters, but the fear it’s instilled and brought about creativity has culminated in a far larger cost: independent thought.

So, isn’t it time we get past arguing about who copied what from where, and instead focus on getting the upper hand—not by striking fear but by equipping ourselves with practical knowledge? Will Pierpaolo Piccioli’s references to Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses lead to some law that requires designers to cite their references? We pray not; designing clothes, after all, isn’t writing a Harvard thesis.

This story first appeared in the August 2019 issue of A.