The world may be your oyster, but for the longest time, the oyster had no place in the realm of emoji. “Why is there no oyster emoji?” asked New York-based restaurateur David Chang in a 2016 Facebook post. Twitter users sympathised: “No oyster emoji I’m being oppressed,” tweeted one; “Crab and shrimp are insufficient,” went another. So Fred Benenson, author and self- proclaimed emoji aficionado, got cracking. In 2017 and 2018, he submitted proposals to the Unicode Consortium, the organisation that governs the emoji universe, for an oyster emoji (complete with pearl, natch). And lo, success! Nature and food enthusiasts, rejoice, for the oyster emoji has finally arrived.

The 🦪 (oyster emoji, for all those who cannot see it) is included in Unicode’s 2019 release of a whopping 230 emoji that are currently winding their way to your choice platform. Announced on World Emoji Day on July 17, this set comprises accessibility icons, animals like the sloth and flamingo, and the wildly adaptable ice cube emoji, among others. It’s indicative of Unicode’s efforts to broaden, enrich, and diversify emoji for global application. “These are symbols that show up on everyone’s phones every day,” Benenson tells me. “They should be representative.”

Indeed, emoji are no longer just an array of happy or sad faces, but a world-spanning range of pictograms that encompass all manner of human expression and experience, right down to the smiling poop. Yes, they still describe basic emotions and furnish visual cues like what we had for lunch 🍕. But even better, they add context and colour to our digital exchanges, while conveying additional layers of nuance — from sarcasm to emphasis — in a single wink. You’ll notice how a “LOL 🤣” is completely different from a “LOL 🙄”.

Which is not to say emoji have emerged as a language per se. Far from it. Benenson prefers to describe emoji as paralanguage, “gestures or facial expressions that act as additions to language”. Likewise, internet linguist Gretchen McCulloch, on an episode of the Emoji Wrap podcast, characterised emoji as “ways that we restore the body to our online communications”. Put simply, they make our digital conversations that little bit more human.

And for as long as people have been communicating via screens, they’ve attempted to insert human expressions and gestures into the machine. In 1982, on an Internet message board, computer scientist Scott Fahlman put forward history’s earliest emoticons, 🙂 and :-(. “Read it sideways,” he handily instructed. They worked. Emoticons grew in popularity alongside Japanese kaomoji such as (*_*), and would grace ICQ messages, MSN chatrooms, and MySpace pages. They signified everything from affection <3 to jokes XD with what folklorist Lee-Ellen Marvin, in 1995, dubbed “winks which signal the playfulness of a statement over the seriousness it might denote”.

That spate of typographic innovation met its match in Japanese designer Shigetaka Kurita, who, in 1999, presented the world with its first emoji (literally, “picture character” in Japanese). It was — what else — a heart emoji. Emoji would be Japan’s best kept secret for more than a decade before it was integrated into the Unicode Standard. In 2010, it landed on Android and iOS platforms, spawning a phenomenal and universal communicative form.

Emoji were so rabidly loved and adopted that by 2016, 92 percent of the world’s population was using it in mobile messages. In quick succession, World Emoji Day was launched, as was Emojicon, the one and only emoji convention. Even linguists and lexicographers were won over: Oxford Dictionaries’ 2015 Word of the Year was 😂 as it “best reflected the ethos, mood, and preoccupations” of that year. Not even 2017’s tepid The Emoji Movie (7 percent on Rotten Tomatoes, LOL) could dampen the hype. Where there were 608 emoji in the first Unicode release, today, that count is upwards of 3,000.

You don’t get to 3,019 emoji without some assistance. Due to its new global presence, the emoji keyboard has had to expand and embrace a planet’s worth of people, cultures and concerns. To do so, Unicode invites suggestions for emoji, which it then considers in accordance to a set of rigorous guidelines. The upshot is a diverse, highly representative keyset where sushi sits alongside tacos, where there’s a ball for every sport, and where skin tones run the gamut.

Leading the charge for emoji inclusivity is Emojination, a group that aspires to “emoji by the people, for the people”, its motto declares. Since 2015, it has mounted campaigns for the hijab, broccoli, and sauna emoji, while on its Slack channel, continues to finesse emoji proposals (piñata emoji, anyone?). For co-founder Jennifer 8. Lee, who also mothered the dumpling emoji, the form has always been a participatory, collaborative medium. “Emoji are a curated digital visual language,” she tells me. “It’s the sharedness that’s part of their charm.”

If emoji should contain, according to Lee, “the voice of the people”, emoji have also shaped and enhanced that same voice. A key Unicode guideline, after all, insists that emoji should not be overly specific: they should have meaning and application beyond their literal one. As we know, 🍆 doesn’t always denote an eggplant. Ditto 💅 and 🥑. Emoji are intended for flexible, versatile use and multiple purposes — which has only made it a ripe channel for creative expression.

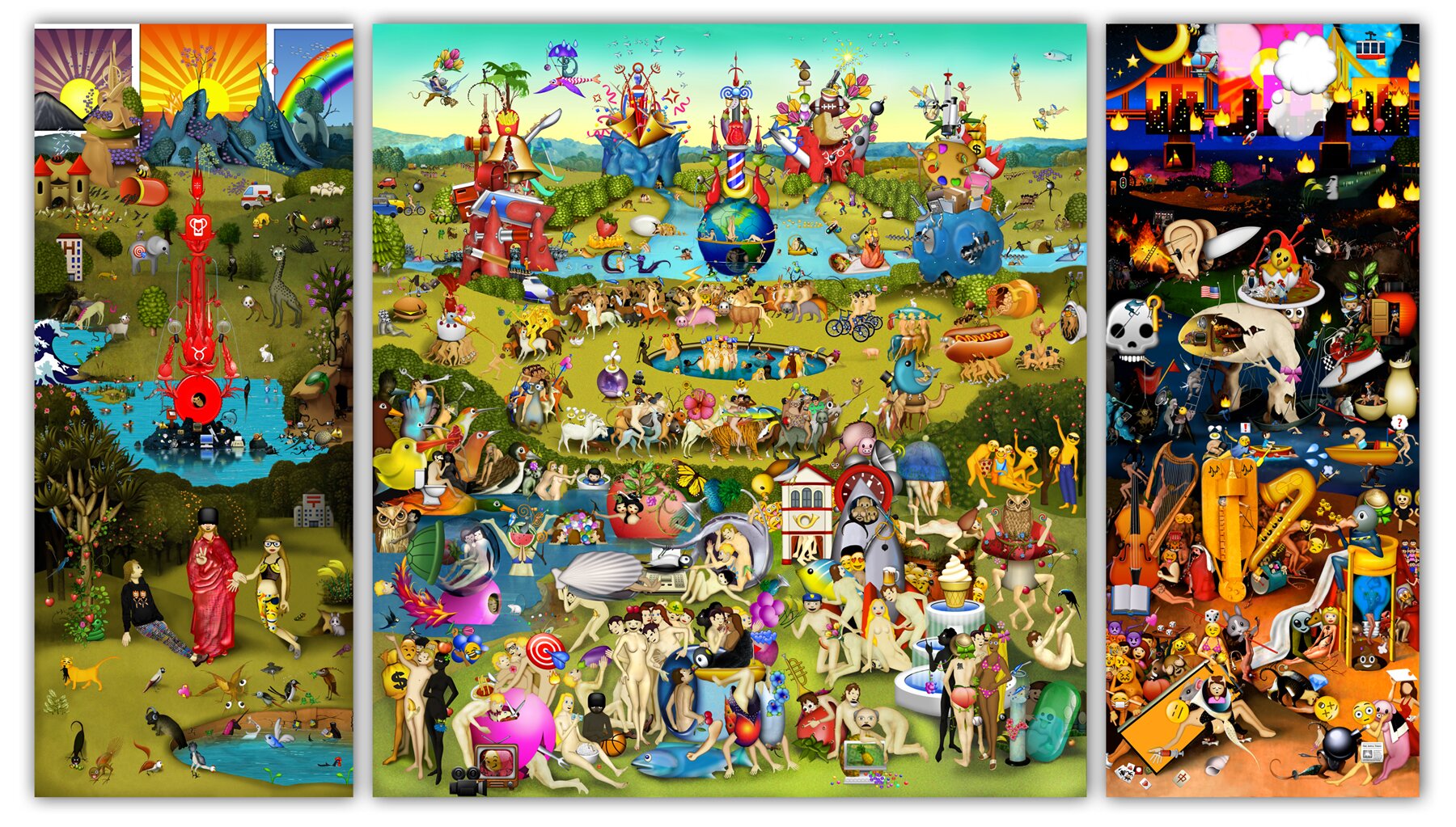

Behold, then, the art form of emoji translation, wherein users render and recontextualise films, books and songs in emoji. There exist emoji versions of Beyoncé’s “Drunk in Love” and Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off”, plus emoji adaptations of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (by artist Joe Hale) and The Shining (by director Jordan Peele). And for something truly otherworldly, there’s Carla Gannis’ 2013 reimagining of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, in which our beloved picture characters are gathered for a bout of unclothed debauchery. “Emoji — which are usually viewed via a sleek, minimalist screen interface,” the artist told Huffington Post, “signify differently when overlaid onto a classical painting.”

But the one translated artefact to rule them all remains 2010’s Emoji Dick or 🐳, which valiantly transforms the entirety of Herman Melville’s opus Moby Dick into emoji. Its mastermind was Benenson (you’ve met him, “the oyster emoji guy”), whose impetus was simply, “How do you take emoji to its logical extreme? What would be the most absurd use of emoji?” Discovering Moby Dick was in the public domain, he crowdsourced the translation work to Amazon’s Mechanical Turk service and funded the entire project on Kickstarter.

Thus, with a “☎️👨🏻🦰⛵️🐳👌” (“Call me Ishmael,” Moby Dick’s famed opening line), the book launches itself into the grey area between absurdist game and conceptual art piece. More strikingly, it captures a visual language striving to, well, make sense. “Emoji Dick is basically unreadable,” Benenson concedes. “The translation is not really successful in the traditional sense. It’s more like a hunt-and-peck method of reading where you can sometimes find really charming versions of the sentence.” It’s true: emoji struggles to translate as much as Ishmael endeavours to grasp the whale’s majesty. “Genius in the Sperm Whale?” he ponders. Or “❗️👌👍🐟⭕️”.

In fact, the reason why Emoji Dick works—why it’s this comic, weird and fun — is its enterprising use (or misuse) emoji as language. Since emoji can’t handle abstraction or grammar, their appearance on a page surprises and amuses. The whole thing feels incredibly novel, a lexical landmark. As linguist McCulloch writes in Because Internet, “Emoji didn’t succeed because they were a language, they succeeded because they’re not a language.” Which is exactly what makes emoji such a compelling medium: it’s so unlike any conventional form that it practically dares users to take liberties with them.

And so we have. For a non-language, emoji has revolutionised online conversations and galvanised artistic expression. As McCulloch put it, “Not everything that’s communication is linguistic.” Any substance or significance emoji might harbour is only limited by their users’ individual or collective imagination. That they’ve been employed to express thoughts, craft narratives, crack jokes, and subtitle Beyoncé is a testament to their boundless expressive possibilities. With a bit of ingenuity and an emoji keyboard, it seems, the world is totally your oyster emoji 🦪.