For an Hermès Birkin bag — that utmost symbol of affluence and exclusivity, so lovingly crafted that it takes 48 whole hours for one to emerge from the workshop — to be casually sliced, carved and cut up to construct a pair of Birkenstock sandals? Outrageous! Plain heresy to anyone with a smidge of appreciation for artisanal, high-end luxury.

But for MSCHF, the Brooklyn-based company behind these lavish leather Birkinstocks (US$76,000/$102,000), it’s just another day at the office.

Perhaps “company” might be too staid a term for MSCHF, which has previously referred to itself as an “Internet artist brand collective”, but that too barely comes close to representing its wildly playful, Internet-baiting business model. As the start-up’s CEO and founder Gabriel Whaley told Business Insider: “Being a company kills the magic. We’re trying to do stuff that the world can’t even define.”

Still, let’s try. Since 2019, the MSCHF team has unleashed an indiscriminate string of projects and products aimed at snaring online interest. It started with a Samsung laptop, installed with six pieces of malware that caused financial devastation totalling US$95 billion, which was auctioned off for upwards of a million.

Then there were Jesus Shoes, Nike Air Max 97 sneakers with soles containing 60ml of water from the River Jordan; All The Streams, a “pirate radio for streaming” and the MSCHF Box, a US$100 mystery crate that may or may not contain up to US$7,000 worth of loot, the twist being that it appreciates in value the longer you leave it unopened. And that’s not to mention absurdist releases like the wide version of the Times New Roman font or the computer programme that generates images of feet.

It’s a varied and assorted output that, nonetheless, has one thing that binds them: they dominate online conversation, going mad viral. But the Internet is no mere channel for MSCHF, it is also, raw material and co-conspirator.

“While it is an insanely efficient distribution vessel for content,” Whaley tells Campaign, “no one has really pushed the envelope of the Internet as a storytelling medium, as an art form.” This explains things like The Office (Slack), which recreated the entirety of the TV series on the Slack platform, and Boomer Email, a newsletter collating real-life email chains, which leans into the Internet’s language and memes, and gains further traction thanks to the breathless press coverage and YouTube discourse that follow.

You can’t ignore the conceptual bent to these releases either. They’re attention-getting stunts that interrogate the nature of attention itself. How else would you explain the existence of something like King of the Clicks, a game that rewards the individual who can get the most clicks? Or what are we to make of Push Party, an app with a single red button that when pushed, does nothing else but sends notifications to other users on the platform?

Whaley, who has a background in marketing, is not unaware of the arms race for online attention (“We’ve hit a peak where the noise is so great on the platforms”) or the unconventionality it takes to draw eyeballs. And through MSCHF, he isn’t shy about cracking a joke in that direction.

“Everything is just, ‘How do we kind of make fun of what we’re observing?’” he told The New York Times.

And MSCHF’s subversions offer reflections beyond the attention economy. The collective’s Birkinstocks outing, for one, is as much a fashion piece as it is an indictment (or literal destruction) of luxury and exclusivity. “Luxury… exists in your head,” Daniel Greenberg, MSCHF’s head of strategy and growth, told Vanity Fair.

“Every watch tells time the same, or every handbag holds the same type of stuff for the person carrying it… but [the question] is: What do you want it to say about you?”

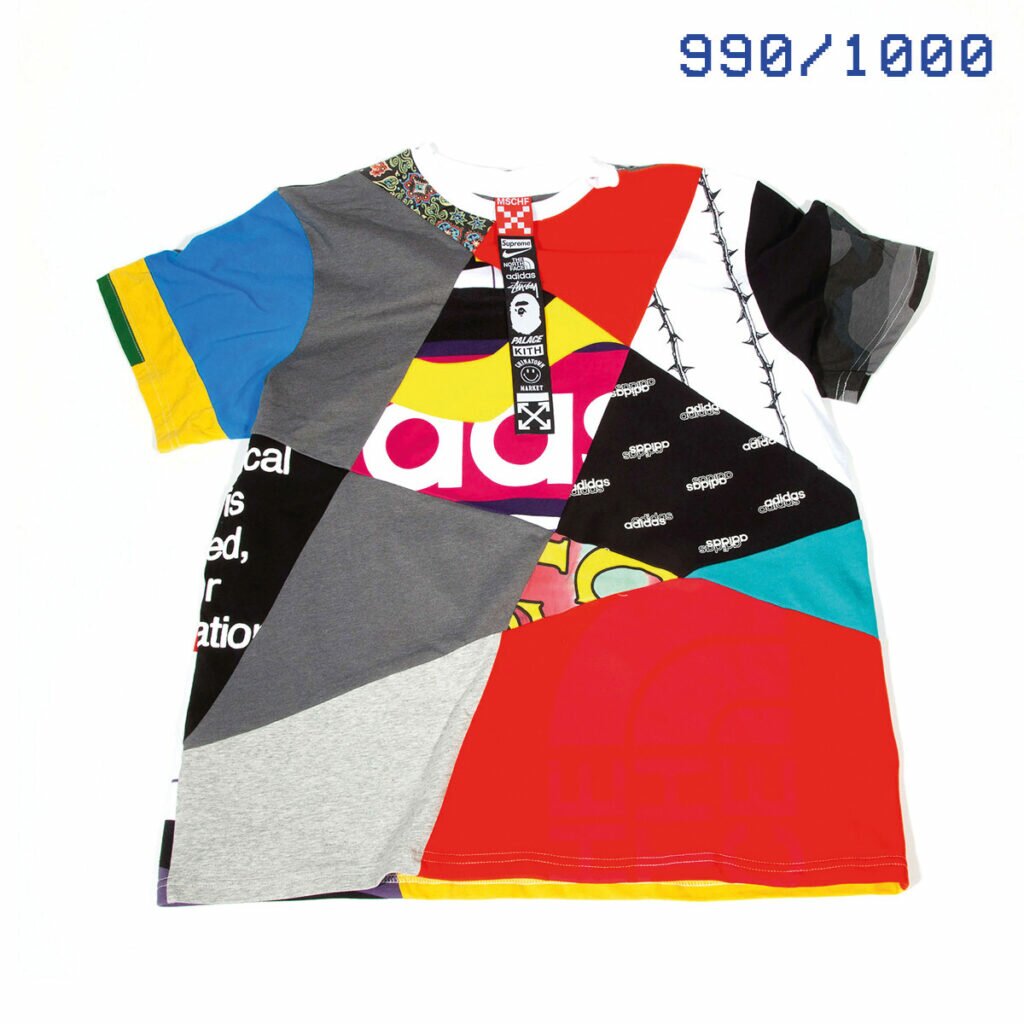

It’s a sentiment that also explains MSCHF X, which saw fabric scraps from 10 streetwear brands including Bape, Adidas and Stussy patched together to form 1,000 collaborative T-shirts — “the platonic ideal of 2020 streetwear in its entirety”. Hypebeasts, as is their nature, pounced because MSCHF just happens to really know its audience.

The brand, after all, is not unfamiliar with hypebeast culture’s “drop-hype product paradigm”, so termed in MSCHF Mag Volume 4. MSCHF unveils its latest goods in Supreme-esque “drops” every two weeks, in limited quantities and for a limited time. It’s a storm that kindles consumer demand, appetite and, yes, attention — just check the subreddit r/MSCHFApp for a real-time feed of the thirst.

But how does all that convert to the bottom line? It’s complicated: MSCHF is tight-lipped about its finances, although US Securities and Exchange Commission filings reveal that it raised some US$11.5 million in outside investments in 2019.

Selling million-dollar malware-infected laptops and pricey sandals does sound like a lucrative model, but MSCHF has not been cheap about giving it away either. Winners of its games like King of the Clicks and Finger on the App (“Keep your finger on the app the longest!”) are ostensibly rewarded with monetary prizes in the region of US$25,000; while participants in its Anti Advertising Advertising Club were paid to post attack ads against “evil brands”.

Then again, while money does drive participation, it apparently doesn’t power MSCHF. In fact, the organisation seems content to “stay outside of the conventional industry framework”, revelling in the freedom of zero accountability to advertisers or “evil brands”. This has allowed for projects such as Walt’s Kitchen, which pluckily skewers Disney, “a monstrous antitrust violation actively blanding culture,” according to Greenberg.

It’s this kind of play that shades MSCHF into the realm of conceptual art, as if this were all but a piece of performance art unfolding in real time, with customers, backers and the media playing their parts to a T. As Whaley cheekily told The Verge: “Our investors know that they’re along for that ride.”

Really, more than a company, brand or collective, MSCHF acts as a band of merry pranksters for whom nothing is sacred — not Hermès products or your favourite Disney characters — and the world wide web is but an invitation to play. There’s notably only so many ways you can pronounce MSCHF.

Whaley himself is cognisant of how Internet content is often wanting in creativity: “What MSCHF does is it’s almost like a punch-up at the powers that be to tell stories in a way that’s more human and less platform-dependent.”

And of course, it’s hard to avoid the Banksy comparison. Greenberg has described MSCHF as the “Banksy of the Internet”: like the British street artist, the collective very much leverages consumerism and the contemporary moment to produce work that is audacious, subversive and ephemeral. In MSCHF Mag volume 4, the brand even landed an on-camera interview with Banksy himself.

Shrouded in darkness to protect his long-held anonymity, the artist dissed Kaws, bemoaned his brand and declared: “People with no imagination of their own are free labour for me.” He then ends the “dumbest f**kin’ interview I’ve ever done” by storming off in (mock?) anger. Was it all a performance art bit? Another stunt? Was that even Banksy? Who knows, but hey, it got your attention.