When her partner, Franco-Iranian photographer Abbas, with whom she had shot alongside for years, passed away in 2018, Singaporean photographer Melisa Teo didn’t think she could bear to pick up the camera again.

It was the trees of Paris that replaced the pillar that she had lost. This month, an exhibition of selected works from her latest book Les Arbres de Paris (The Trees of Paris) opens at the Alliance Française de Singapour. “With them,” she says of the trees, “I learnt to listen to the silence, see the invisible and embrace solitude, rather than run away from it.”

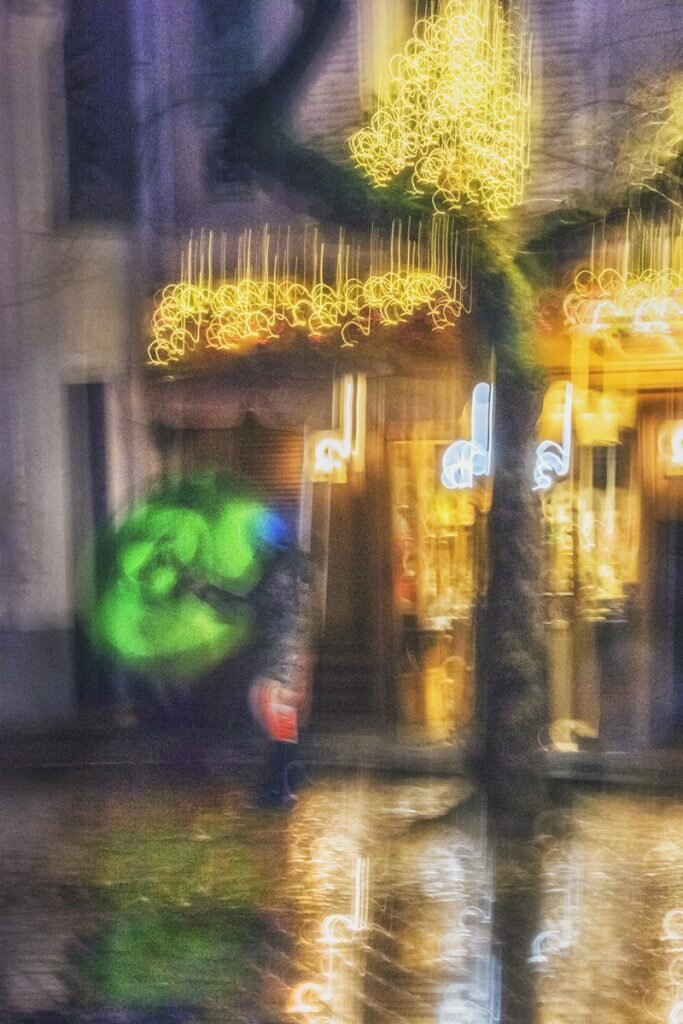

“Melisa’s photographs reveal what the eye doesn’t even suspect. Trees radiate. They are crowned with radiation. They are enveloped by waves. One might call it diaphanous gossamer at times, or a pulsating veil; Melisa prefers ‘a vortex of energy’,” says author Sylvain Tesson of the works.

The French écrivain-voyageur, known for basing his writings largely on the personal experiences of his journeys, wrote the foreword to the new hardback that features 54 images Teo shot at locales such as Champs-de-Mars, Sacré-Cœur and Jardin des Tuileries.

Known for painterly imagery captured on a slow shutter speed for a blurred but evocative quality, Teo honed her aesthetic and camera technique on the go. It was in 2007, when as a book editor curating thousands of photographs for the Editions Didier Millet publication Thailand: 9 Days in the Kingdom that she felt an overwhelming urge to shoot.

“I rushed out and bought myself a camera. I needed to see the world anew — through the viewfinder — and understand my place in it,” she recalls.

By 2011, she had staged her first joint exhibition with Abbas, with whom she made countless photographic trips, to locations such as India, Nepal and Thailand. As the Magnum photographer once told The Straits Times, “It was her eyes and heart, the way she photographed intuitively which made me decide to invite her on my trips.”

Now in his absence, she has drawn strength from meandering through the gardens of her adopted city, Paris.

Of her latest series of works she says: “ If the trees of Paris were substitutes for the metaphysical, then the gardens of Paris were my shrines. I spent days walking in them, finding consolation and company in their living deities. They became my faithful companions, always there, standing in for the absent ones whose presence I missed.”

You bring a very vivid, painterly quality to your imagery. How would you describe your signature style of photography?

I regard my camera as my “third eye” — the eye of intuition, which is honed by meditation and guided by light. Intuition is inner knowledge without conscious reason. The “third eye” perceives a situation long before the naked eye has time to make sense of it.

I like to leave the camera’s “eye” open for longer, in order to give more time to an invisible world of energy and emotions to render itself in the form of light and colour on the camera’s canvas. If “photo” is “light” and “graphy” is “writing”, and “photography” is read as “writing with light”, it could equally be interpreted as “written by light”. The camera is to me a transmitter and translator of light’s messages.

Shooting photographs in this way also helps me blur lines, borders and boundaries. In the meditative state, we are all connected to one another and a greater universe. We are all light and colour.

You often speak of a spiritual link between man and nature, and that the camera is a unique tool that illuminates this for the viewer. What do you mean by this?

Man is a part of nature. We are not separate from it. This is evident in the close relationship all life on earth share with light — we are powered and guided by it; our existence depends on it. Thus, the camera — a medium of light — is in my view, the perfect channel through which man’s innate but invisible connection with nature can materialise.

And how did this fascination between man and nature come about?

It really started in 2016 with my project Eden. I found that I was at my creative best when I worked in nature. The animists believe that all nature — from plants to animals, mountains to rivers, rocks to stars — have a spirit. I felt engaged in an unspoken dialogue with them. So I tried to translate the joy that I felt in their company into images. In so doing, I am also able to better understand spirituality through my own creative process.

You’ve also travelled the world documenting spirituality and faith. Has this informed or changed your views on life?

I have learnt to distinguish the religious from the spiritual; to try neither to indulge in blind faith nor “bad faith”, as defined by the existentialists. I would never denounce the existence of God. Yet I don’t wish my actions in this life to be determined by the anticipation of judgement in an afterlife either.

For years you travelled and shot with Abbas. Though your styles are different, did he influence your approach?

Abbas is my greatest influence. He changed my view on life and that translated into my images.

Having dedicated most of his career to documenting religions, he used to say that his relationship with God was “purely professional”, while I liked to assert that mine was “purely personal”. But I saw in him a true believer of the human potential, whose limits he challenged every second of his life. His photos are as stark as he is honest, as complex as he is profound, and as subtle as he is discreet. To me, he was a prophet who practised without preaching.

Our styles may be poles apart — his black and white and sharp, mine in colour and more than slightly out of focus — but we are both looking for the same thing: to transcend reality, rather than replicate it.

It would be safe to say that we both agree on art being the highest form of spirituality.

What drives you? Is it the creation and the art, or the documentation and the research?

The creative process is what drives me. I seek to transcend reality even at the risk of ruining many of my photographs because I believe that it’s worth it if synchronicity between my subject, myself and the world around us finds its way into the frame and the perfect picture is revealed. Have I chosen the image, or has the image chosen me?

Tell us a little about your life in Paris.

I manage Abbas’ photographic archives through Fonds Abbas Photos, which has been created to protect, preserve and promote Abbas’ work. We continue to give it a voice through new cultural projects such as books, films and exhibitions.

I have also been studying French and was able to write Les Abres de Paris (The Trees of Paris) in both languages. French is one of the languages where the word “culture” designates both matters of the mind and matters of nature. And the tree does indeed resemble the mind. As Voltaire famously wrote: “we must cultivate our garden”. Just as trees need to be constantly cared for and tended to in order to grow in full glory, so too the human mind is able to unlock its full potential through constant learning. By keeping the company of books and trees in Paris, I was alone but not lonely.

Melisa Teo’s solo exhibition Les Arbres de Paris (The Trees of Paris) runs until 19 December 2020 at the Alliance Française de Singapour. She leads tours of the exhibition on Saturday afternoons. Click here to reserve a place. A special screening of the documentary film Abbas by Abbas will also be held on 10 December, 8pm at Le théâtre, Alliance Française de Singapour.