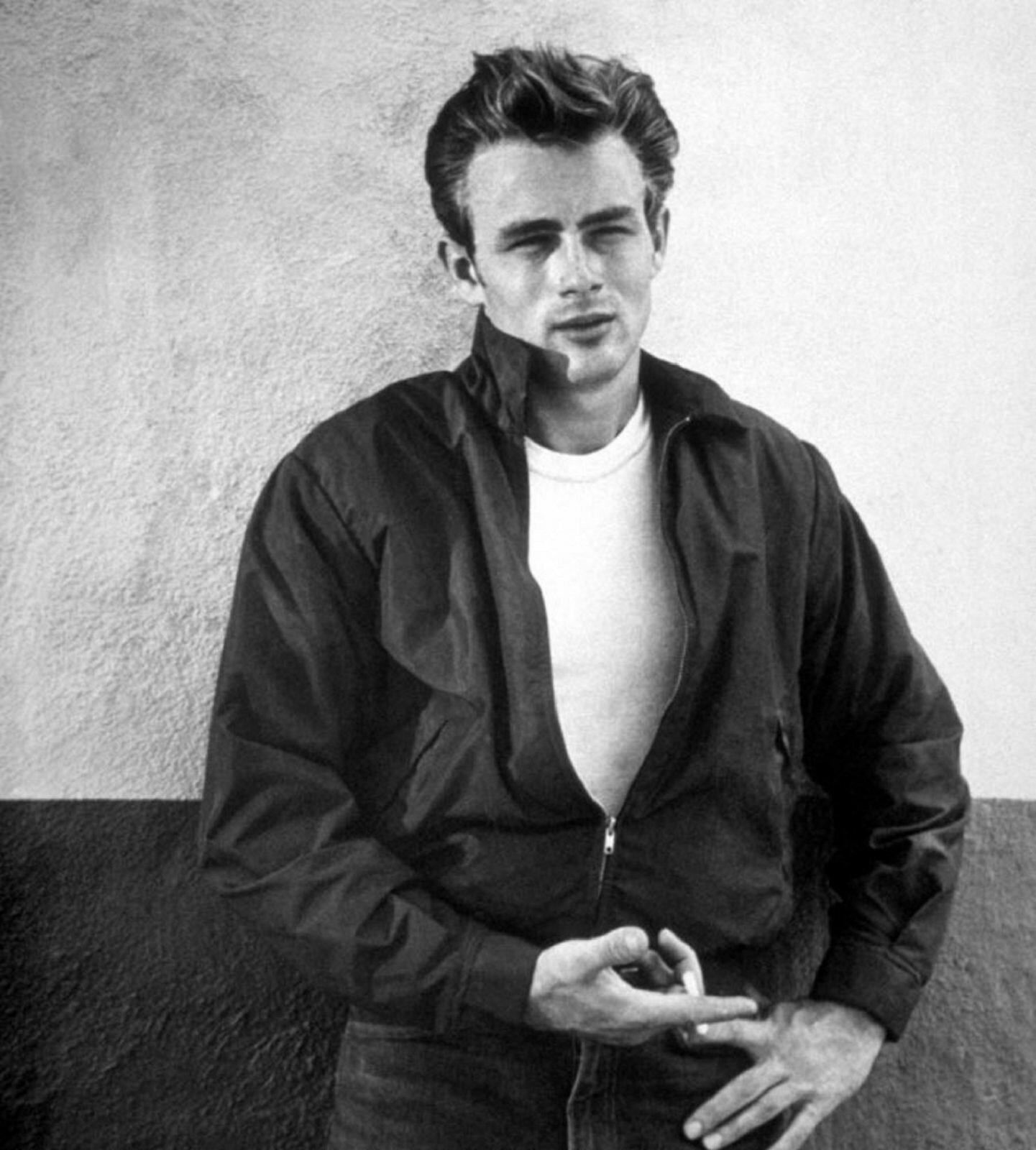

James Dean is dead, long live James Dean! The celebrated American actor may have starred in a mere three films in his brief lifetime, but more than half a century after his death, his cinematic output has only picked up. Of late, Dean has been cast in the upcoming Vietnam war drama, Finding Jack, where the problem of him being dead will be neatly resolved with computer-generated imagery. Yes, the late actor will be recreated in his fullbodied glory with visual effects and deep technology cobbling together existing photos and footage. With that, directors Anton Ernst and Tati Golykh are promising us “a realistic version of James Dean”.

The filmmakers might be among the few not creeped out by the idea of a CG James Dean (Chris Evans deemed it “shameful”), insisting that only JD could pull off the movie’s “extreme complex character arcs” — which is a bizarre thing to say about a digital creation unburdened by complexity or character. Either the directors have an abiding faith in their tech or presumably, Ryan Gosling was unavailable.

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy)

But that’s cinema technology for you in the twilight zone of Hollywood. Filmmaking effects and innovations — from motion capture to digital modelling — have advanced such that they’ve long ago caught up with life and death. It’s never been farfetched to imagine that the tech that brought us CG creatures like Gollum (The Lord of the Rings) and Neytiri (Avatar) would eventually take on humanity, presenting us a young-looking Jeff Bridges (Tron: Legacy), an old-looking Chris Evans (Avengers: Endgame) and an undead James Dean.

In fact, as far back as the ’60s, computer graphics trailblazer John Whitney Jr was already envisioning a future where digital effects could “create the likeness of a human being”. He divined: “We may be able to recreate stars of the past, cast them in new roles, bring them forward into new settings if stills and old films can be used to make the likeness.”

At least one person took that to heart: George Lucas, who, in 1975, founded Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) to develop the visual effects for Star Wars. The relentlessly innovative VFX company pioneered tech such as motion control, digital compositing and Go motion in its pursuit of Lucas’ “immaculate reality”. By 1981, the filmmaker was confident enough in ILM’s computer effects to declare to Time, “Revenge of the Jedi will be the last picture we’ll shoot on film.”

-

The de-aged Carrie Fisher and Peter Cushing, both in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy) -

The de-aged Carrie Fisher and Peter Cushing, both in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story.

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy)

Not so fast, George. It’s taken a while, but the latest batch of Star Wars pictures, though shot on film, effectively realise Whitney’s prophecy. In particular, 2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, set in the period before the first trilogy, made quick work of the ravages of time. Using motion capture and digital recreations, ILM reanimated the late Peter Cushing so he could “reprise” his role as Grand Moff Tarkin, then de-aged Carrie Fisher to make like it’s 1977. While technologically groundbreaking, the performances were controversial (“a digital indignity” per The Guardian) and ultimately, made for uncomfortable viewing (“jarring”, said USA Today). Not surprising: While these CG characters may somewhat pass for humans, their waxy skin and fluid gestures are unnerving giveaways, conveying not emotion but emotional distance.

As David Fincher, not one to mince words, observed in Film Comment in 2009: “All of the beautiful things that really talented animators bring to their craft ultimately are obfuscation when you’re talking about a performance.” His topic then was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, for which Brad Pitt was aged, deaged and digitally manipulated up to his eyeballs. Nonetheless, Digital Domain’s age-defying CGI was realistic enough, largely because it was translated from Pitt’s performance rather than wholly generated with animation.

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy)

It must help not having to work with the dead. Benjamin Button wasn’t the first movie to digitally youthen its star (2006’s X-Men: The Last Stand has that honour) and it definitely wasn’t the last. In 2019, the increasingly seamless tech gave us a young Robert De Niro in The Irishman and a Fresh Prince-era Will Smith in Gemini Man, among others. Marvel films, too, have gifted us curious sights like that in Ant-Man of a digitally aged Hayley Atwell interacting with a de-aged Michael Douglas. Today, a performer’s age is just a number waiting to be reset.

But is any of this so bad? After all, cinema is deathless, a medium made for immortality. On film, stars live on forever in their youthful heyday, at peak performance, in enduring cultural posterity. As James Dean once proclaimed: “If a man can bridge the gap between life and death, if he can live on after he has died, then maybe he was a great man.” If digital effects can recapture youth and life on screen, shouldn’t filmmakers hop on that bandwagon?

Well, it’s not their call to make. While Fisher and Pitt gave the go-ahead on their digital makeovers, James Dean isn’t around to give his say-so. He may have aspired to immortality at age 24, but there’s no knowing if he’d happily participate in a posthumous puppetshow. It’s one thing to create for yourself an undying cinematic legacy and quite another to be digitally revived generations on, as Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire have been, to advertise chocolate and vacuum cleaners. Not for nothing did Robin Williams lock up the rights to his image in a trust until 2039.

-

In Ant-Man, a digitally aged Hayley Atwell interacts with a de-aged Michael Douglas.

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy) -

Tom Hanks with John F Kennedy in Forrest Gump.

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy)

Plus, let’s face it: a CG performer is but a meagre replacement for the real thing. Hollywood surely doesn’t lack for talent ready to be cast as youthful versions of De Niro and Linda Hamilton, or to step into roles left vacant by the deceased. The idea that films should be showcases of more humanity and less fancy technology isn’t a radical one.

But cinema is also a looking glass. In a time where artificial intelligence and machine learning are trending, where virtual and augmented realities are handily accessible, a post-death James Dean is par for the course. Trailing a slippery slope, cinema and technology have arrived at extremes. Note the 2013 sci-fi outing The Congress, which imagined exactly such a world, where performers willingly scan their likenesses into a database to be exploited for all eternity (spoiler: it’s a dark film). We can’t stop the advances of filmmaking technology, but more so, we can’t stop interrogating its ethical, legal and artistic implications.

That’s because there’s more to come: Worldwide XR, the company behind CG James Dean, has acquired the rights to represent over 400 other late historical figures including Lana Turner, Christopher Reeve, Malcolm X and Amelia Earhart. Macabre, much?

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy)

Then again, we were given notice. In the Oscar-showered Forrest Gump, we’d already watched Tom Hanks, as hero Gump, meeting the dearly departed likes of John Lennon, and US Presidents John F Kennedy and Richard Nixon. These fictional encounters were made possible by ILM massaging archival footage with techniques like image warping and chroma key, while Hanks performed his parts in front of a blue screen. “They tell you where to look and when to turn,” he told NBC in 1994 of the process. “I’m an automaton.”

At the time, the effect was a neat enough gimmick; Hanks judged it “unbelievable”. But when asked to ponder a hypothetical future where he himself might be digitally restored to life, the actor was unequivocal. “That,” he said, “would be the worst possible tragedy imaginable.”

(Image: Drafthouse Films, Jerry Bruckheimer Films/Alamy)

This story first appeared in the March 2020 issue of A Magazine.