Imagine sitting down at a restaurant and enjoying a plate of succulent fried chicken. Nothing strange about that, but what if, after you finished eating you could walk outside and meet the chicken you just ate as it struts around pecking for grain?

It might sound like something from a science fiction novel, but it’s already a reality. As of last December, you can sample chicken nuggets made from meat grown from the cells of a living chicken right here in Singapore at the restaurant of member’s club 1880.

“We wanted to tackle the assumption that you need to kill an animal to eat meat,” explains Josh Tetrick, CEO of Eat Just, the US-based company behind the futuristic lab-grown chicken. “Now we’ve managed to change that.”

It’s a significant milestone that makes Singapore the first country to approve the sale of any clean or lab-grown meat product. And while Impossible Foods and Beyond Meats might be making headlines with their plant-based burgers, Singapore is fast becoming a pioneer when it comes to what we might all be eating in the future.

Lobster harvested in a lab, “pork” made from jackfruit, milk from stem cells and fast-growing fermented fungi are just some of the futuristic sounding foods currently being developed by local start-ups such as Shiok Meats, Karana and TurtleTree Labs.

“They’re very aligned to building a robust food system in Singapore; they’ve created a very conducive environment,” continues Tetrick during a Zoom call from his current base in Hawaii.

Eat Just found it so conducive, it recently entered into a joint partnership with local food-focused investment firm Proterra Asia to spend up to US$120 million ($159 million) on a facility in Singapore to produce its plant-based Just Egg, which has already sold the equivalent of over 60 million eggs globally.

Attracting overseas biotech firms and supporting local food tech start-ups is a key part of Singapore’s drive to produce 30 percent of the country’s nutritional needs locally by 2030 — it currently produces just 10 percent. It’s a direct response to concerns over future food security.

“Singapore is vulnerable to food security issues, but we can turn these challenges into opportunities through R&D,” states Dr Hazel Khoo, executive director of the Singapore Institute of Food and Biotechnology Innovation (SIFBI), which opened last year as an offshoot of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star).

To help tackle those challenges, $144 million of research funding was made available in 2020 through the Singapore Food Story R&D programme, led by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) and A*Star.

“The reality is the research is incredibly expensive” says Patrina Phua, CEO and founder of local biotech company Eatobe, as she takes me on a tour of the SIFBI research and development facility, located on the fourth floor of a gleaming office block in One North.

“Our current progress just wouldn’t have been possible without access to this research facility,” she continues, indicating a room housing $1 million worth of food analysis equipment designed to identify micrograms of individual nutrients.

Through a joint agreement with A*Star, Eatobe’s team of PhD scientists have been able to use the state-of-the-art facilities, which they share with 10 to 15 other local biotech start-ups, since 2018.

The inspiration for Eatobe, which is short for “eat to be free”, came to Phua while working as a civil servant for Enterprise Singapore. Involved in logistics and attempts to tackle the huge issue of food wastage in India, she realised it would be easier to simply make food more nutritious.

“It’s not about making more food,” says the 33-year-old. “It’s about making food more efficient.”

After realising there were no ready made solutions available, she decided to start Eatobe in 2016. Since then, her team has been researching sustainable ways to extract and generate more nutrients from various plant products like nuts, grains and fungi and, most recently, fish skin.

One solution they’ve trialled is using fermentation techniques to boost the production of mushrooms, accelerating growing cycles of between three and six months to just four days, while extracting additional minerals and vitamins.

They are also identifying lesser-known species as new sources of plant protein and are working with a Malaysian farm to grow water lentils as an alternative to leaf crops like spinach. Whereas spinach takes two to three months to grow, water lentils can double their biomass in 48 hours and contain 40 to 45 percent more protein.

“The aim is to find plants that are climate tolerant, fast growing and little used,” states Phua, before explaining that planting more diverse crops can help address pressing environmental issues such as deforestation and soil erosion.

“The ultimate aim is to disrupt the focus on ultra-processed foods,” she proclaims of her long-term goals for the company. “Food is a right, not a privilege. That means giving people basic access to nourishing food that’s nutritious, not laden with chemicals.”

The company, which has already raised around $1 million in investment, is planning to launch a breakfast cereal whose natural ingredients have been treated to allow babies’ stomachs to better absorb the vitamin B and iron they contain.

They are also relocating to a new facility in Boon Lay, as part of a new partnership with global seafood producer Fish International Sourcing House Group.

As well as continuing their existing research, they plan to start extracting collagen from the waste products (specifically fish skin) generated during the production process.

“We believe that what can be harvested as food for human consumption should be,” says the avowed pescatarian.

Eatobe isn’t the only local food tech company currently expanding. Life3 Biotech, which has developed its own proprietary plant protein extract called Veego, will open a 50,000-sq-ft agri-food pilot facility in Paya Lebar in the second half of this year. Developed with the support of SFA and the Singapore Land Authority, it will be the first of its kind in the country.

When up and running, Life3 Biotech CEO Ricky Lin estimates that the facility could produce up to 150 tonnes of plant protein a month. It marks the achievement of Lin’s original aim when starting the company back in 2015.

“Fundamentally, my ambition was to solve a real life issue, namely creating an ethical and nutritious protein source that could be produced securely in Singapore,” states the enthusiastic 39-year-old, who admits it was his battle with obesity as a child that first made him start to really consider what he ate.

A science graduate from the National University of Singapore, Lin started small, personally developing the formula for what was to become Veego in borrowed lab space at his old university. He admits it hasn’t always been easy and it was the support of his wife that stopped him quitting on a number of occasions.

“Back in 2015, the whole ecosystem wasn’t as developed as it is today,” recalls the father of two, who had to use his own savings to finance the research.

“Even my parents were asking why do this when there are already people producing mock meat?”

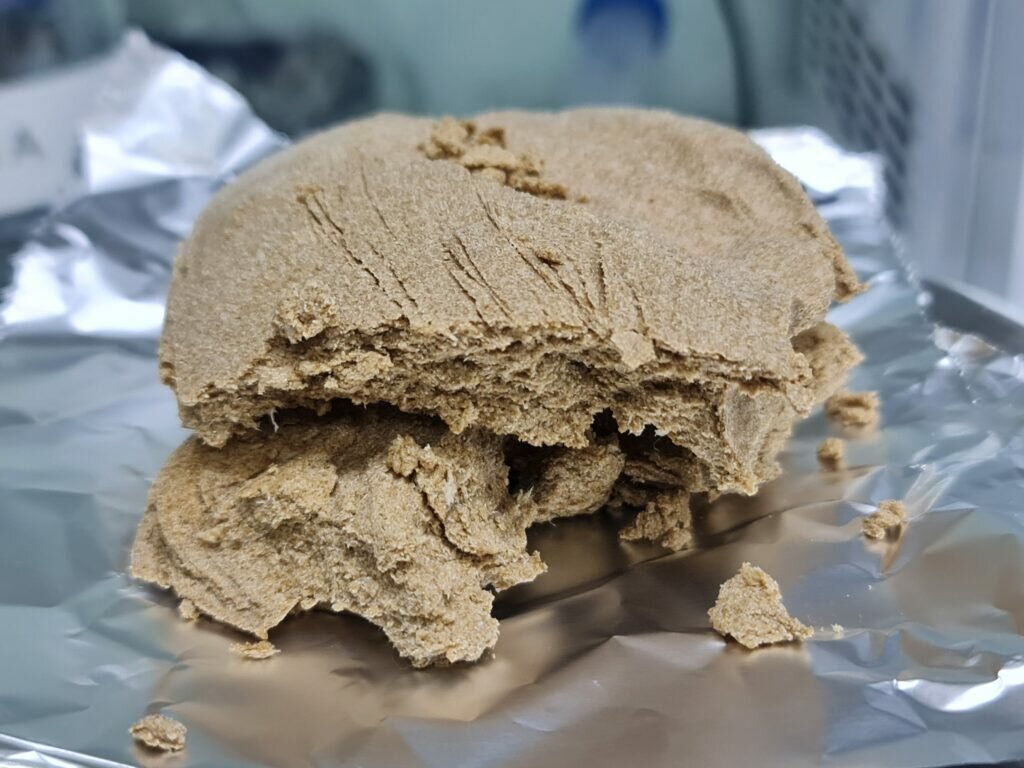

Made from mushrooms, peas, soya and micro-algae, Veego is high in protein and fibre, low in allergens and preservative free. Lin is adamant that it’s not a meat replacement but a similarly textured healthy alternative that can be supplied either cubed or minced. This versatility makes it suitable for various uses, making it particularly attractive to food manufacturers.

“We very much see ourselves as the Intel inside,” says Lin, revealing that the company is keen to focus on a B2B business model. He confirms that they’ve already had conversations about supplying to leading brands and have a number of businesses, from food manufacturers to restaurants, waiting to purchase their product when the factory goes online. He sees the next logical step as scaling up production and exploring opportunities to export Veego.

However Lin, who became vegetarian after visiting commercial farms for his former job in the armed forces, is pragmatic when considering the growth of the industry as a whole. He points out that the current market for plant-based and clean meats in Singapore is small and that it’s unrealistic to think they might replace the real thing anytime soon.

“Alternative options might be more available globally nowadays, but we can’t delude ourselves into thinking we’re winning yet,” agrees Eat Just’s Tetrick. “The reality is there are still more people eating meat today than there was yesterday.”

Yet, despite this current reality, the former Fulbright Scholar does believe change is possible. “Of course, there’s still work to be done, but the good news is, the nuts and bolts, the technology to make it happen is already here,” Tetrick states, before pointing out that the next generation of consumers are less hesitant about trying alternative food sources. “You tell them this chicken is from cells and no chicken dies and that’s it, they get it; it takes three seconds.”

Talking to Tetrick, it’s clear that like other food tech innovators, he has a genuine desire to reinvent and disrupt the current global system and build a more restorative alternative, one that is ultimately more ethical, healthier and more sustainable for everyone involved, including the animals.

Better treatment for animals was a major inspiration for Sandhya Sriram and Ling Ka Yi, co-founders of Shiok Meats. The company, which launched in 2018, made international headlines last November for producing the world’s first cell-based lobster meat.

“I’ve been a vegetarian all my life for ethical reasons and I am a stem cell scientist by training,” says Shiok Meats CEO and co-founder Sriram, explaining how they first started.

“Back in 2014, I came across the idea of cell-based meats and I became obsessed with the concept as an alternative solution.”

The decision to concentrate on cell-based seafood was partly because no other clean meat company was doing it, but also due to the huge demand for seafood in the Asia Pacific region, a demand which has led to unsustainable practices in the industry.

“We wanted to create meat that is healthy and environmentally-friendly that’s just as tasty and nutritious, but without involving any animal cruelty,” says Ling of their initial decision to focus on lab-grown shrimp.

Having garnered $12.6 million in funding last year, the company is now working on reducing the price point and increasing scalability of their different seafood options. According to Sriram, they hope to launch their ethical seafood in restaurants by the end of 2022, with the longer term goal of being stocked in supermarkets within the next five years.

While the time frame for this food revolution may not be set, it’s apparent that clean meats and plant-based proteins are going to become an increasing presence on our plates in the coming years. A combination of government support, technological know-how, passionate entrepreneurs and an increasing awareness among consumers suggest we may be reaching a tipping point in how we think about food and where it comes from.

“There’s an opening,” says Tetrick. “It definitely feels like there’s a chance to live in a world where we don’t have to kill billions of animals. We don’t have to destroy rainforests just to enjoy a chicken dinner.”

This story first appeared in the March 2021 issue of A Magazine.