What do the Regent Singapore, Wing On Life building and the old National Library on Stamford Road have in common? They are all modern buildings and some of the most significant ones in Singapore.

The organisation that identified them is Docomomo Singapore (DocomomoSg), an under-the-radar group that was accepted by Docomomo International in December 2020 to establish the local Chapter.

Don’t be fooled by the outré abbreviation; the non-profit that’s headquartered in Lisbon, Portugal, is actually the International Committee for Documentation and Conservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement. This status upgrade is significant because Singapore is one of the most modernist cities in the world and has a veritable treasure trove of buildings with this architectural style.

Unfortunately, the country’s insatiable appetite for progress, economic development and all things contemporary has meant the demolition of many such buildings, with many more under threat.

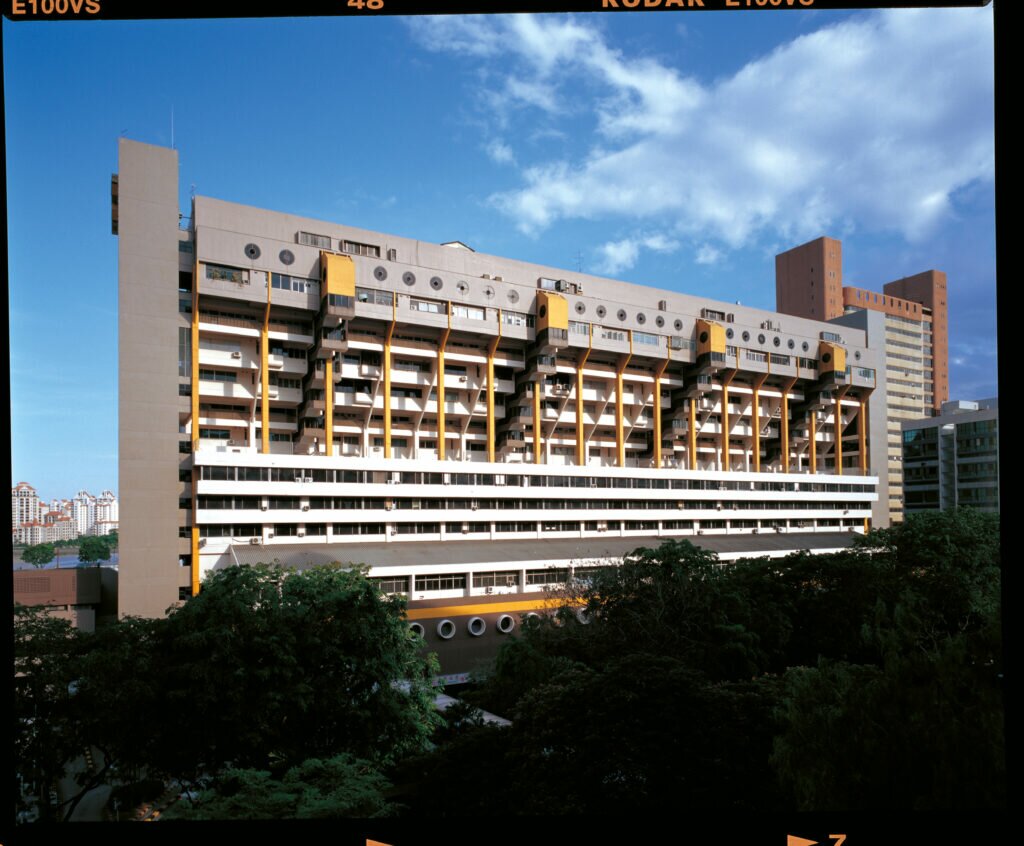

Of the former, the old National Library, Pearl Bank Apartments and Shaw Tower are examples; of the latter, People’s Park Complex, Singapore Science Centre and Pandan Valley Condominium are examples. Topping the list of endangered buildings was Golden Mile Complex, until the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) announced last October that it was being proposed for conservation.

Among those frantically working behind the scenes to rally URA to achieve this outcome was DocomomoSg, even though it was then only a Working Group-In-Progress.

“Along with other groups like the Singapore Heritage Society, I think we were probably among the culprits behind URA’s decision,” says Ho Weng Hin, chairperson of DocomomoSg and founding partner of Studio Lapis, which specialises in architectural conservation.

One of the things it did was to work with a private engineering firm to carry out a preliminary study to assess the feasibility of rehabilitating the complex as well as understand how it can undergo adaptive reuse.

All For Good Reason

Tempting as it is to dismiss all the hullabaloo around this issue, DocomomoSg cautions against it, and rightly so. After all, modernism is very much ingrained in our urban fabric, even in the slab and point Housing and Development Board apartment blocks and the community centres scattered throughout the heartlands.

Another compelling reason is encapsulated in the definition of the modern movement within the local context. From the 1950s to 1980s (even up to the 1990s, if used loosely), it coincided with Singapore’s rapid urbanisation after the British withdrew its colonial hold and later, when it gained independence.

As a result, a slew of buildings, both public and private, were designed and constructed: Asia Insurance Building in 1955 (conserved), National Theatre in 1963 (demolished) and Rochor Centre in 1977 (demolished).

“These modern heritage buildings are physical representations of our city’s phase of nation building, by local architects and developers,” says Karen Tan, treasurer of DocomomoSg and founder of indie cinema The Projector.

“They encapsulate both a national narrative of aspiration towards forging our own modernity as well as a local architectural narrative of an urban response to tropical architecture.”

Indeed in their time, many of these buildings were recognised for their innovative architecture and engineering, and have now become time capsules for subsequent generations to understand and experience the creativity of the modern movement.

For example, Pearl Bank Apartments, designed by architect Tan Cheng Siong, was an important prototype for high-rise, high-density urban living. While it stood, it was studied and feted by architects, planners, urbanists, architectural historians and heritage enthusiasts both as an elegant solution to applied urban research and experiment, and for its bold modernist aesthetics.

Not to be overlooked either is how these buildings accrued urban significance by marrying extreme urban intensification with high-quality living spaces, which served to transform the way Singaporeans live, work and play.

“Our modern buildings became the manifestation of Singapore’s experimental urban renewal programme under the Government Land Sales that shaped the city’s future,” says Ho.

Tan adds: “These buildings, such as Golden Mile Complex and Golden Mile Tower, are also a social asset, having accumulated a rich patina of social memories over time, as their uses have evolved through the ages. It is these that give cities a sense of character and a uniqueness that cannot be replicated elsewhere.”

Rooted In Conservation

The idea of forming an organisation like DocomomoSg was triggered when the sale of Pearl Bank Apartments was announced in 2018. Ho and a group of like-minded professionals immediately formed the Working Group-In-Progress and met with buyer CapitaLand and URA, offering to undertake the feasibility study of an adaptive reuse scheme.

“We did not want to later regret that we did not do anything when we could, so we thought to give it a shot, despite knowing it was likely a losing battle.”

“We were quite experienced in fighting battles with a long shot [of winning]. Some of us tried to save Dakota Crescent and the old National Library. With the latter, it was almost certain to be demolished but we did not want it to go without a fight; we wanted the authorities to register the unhappiness among the public and understand the significant loss.”

In just over half a year, a technical solution was offered for Pearl Bank Apartments, but it was deemed financially unviable and CapitaLand eventually demolished the iconic building.

Undeterred, Ho says they decided to propose Singapore as the location for the 2019 edition of the mAseana (modern Asean architecture) International Conference. Part of a five-year project initiated by Docomomo Japan and the Japan Foundation, it is also supported by Docomomo International.

He feels that the conference played a major role in highlighting the need to conserve Singapore’s modern built heritage.

“I think that the loss of Pearl Bank Apartments caught everyone off guard and the authorities are determined not to lose another building of similar significance.”

“Consequently, the conference became not just another academic discussion, but we managed to get funding and support to fly in our carefully picked experts, who actually had closed-door engagements with URA and the Ministry of National Development.”

One of them was heritage economist Donovan Rypkema: “We must face up to the economic angle and not pretend it doesn’t exist or is something evil; it is very real and needs to be addressed.”

Since then, DocomomoSg has been keeping busy, primarily in four areas: research, education, advocacy and outreach, membership and fundraising. One of its immediate tasks is to launch an inventory of 100 significant modernist buildings in Singapore, spanning pre-WWII to the early 1990s, on a dedicated website. DocomomoSg hopes this will facilitate future research and collaborative projects with institutions, private set-ups and the public.

The executive committee is formalising the membership tiers and benefits, and planning a membership drive and activities for the year ahead to raise awareness of the country’s modern built heritage. When leisure travel is allowed, Ho is even thinking of collaborating with other overseas chapters to arrange symposia and tours of sites in their respective countries.

“Modernism is everywhere. You just need to open your eyes and look around; this is a theme we want to reinforce and help substantiate our stance that they should be conserved and not destroyed.”