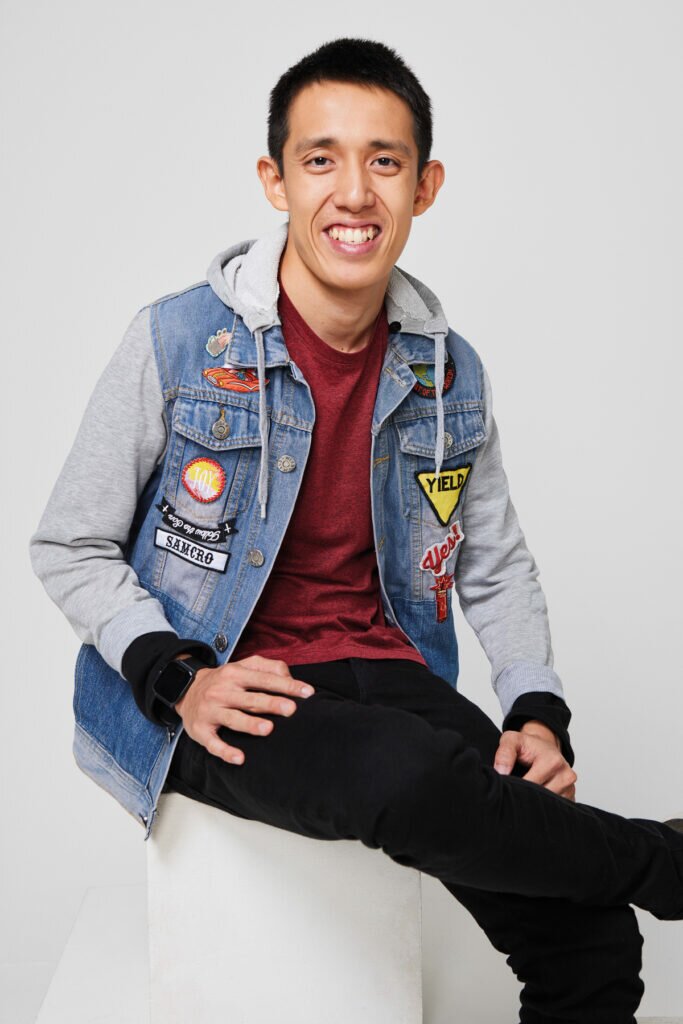

Joshua Lum has put his arm around distraught migrant workers trapped in a gyre of injustices. Among the friends he’s consoled is a construction labourer who’d paid substantial agent fees to secure a job, only to discover discrepancies between what was promised and his actual salary and working hours.

“He cried to me over the phone; how could this happen to him, given that he’d been in Singapore for eight years and knew the system well?” relates the rangy millennial.

It’s a well-worn tale laced with pathos, but one which has drawn greater awareness in a pandemic that has thrown migrant worker welfare firmly into the spotlight. Overnight, reports of foreign construction labourers sequestered in dormitories under untenable living conditions triggered a gush of support from solicitous individuals. A community even went into overdrive with their care packages and outreach efforts.

Underlying the debate over greater parity and who should pay for it is the larger spectre of unethical employment practices plaguing the country’s transient workforce. A 2021 report by the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME) suggests that migrant domestic workers typically pay their agents six to eight months of salary to secure a job in Singapore. In the absence of a breakdown of their expenses, overcharging is prevalent. The problem affects all sectors, including the domestic and construction sectors.

There may be a sea change afoot, however. Buoyed by pandemic-induced digital transformation and tightened regulations, tech-savvy social entrepreneurs are working to steer migrant employment towards a less unscrupulous paradigm.

Onboarding The Undeserved

One such change maker is Lum, whose fledgling social enterprise Sojourner Brother is about to launch a web-based app connecting migrant labourers to potential employers — sans the extortionate recruitment fees. The platform, positioned as a matching service rather than an employment agency, aims to facilitate transparent contractual agreements between employers and workers — at a flat $30 to $50 transaction fee borne by the former. In the offing is a facial recognition-enabled tool to help labourers track their completed work hours, which Lum hopes can help solve pervasive salary disputes.

“A lot of times, migrant workers check in and out of work by signing some sort of logbook that only employers have access to,” he explains, adding that a dearth of tangible evidence required to prove their case routinely kneecaps migrant workers.

“As volunteers, a lot of workers come to us with scraps of paper that don’t really hold much ground, so we want to help them build a case. In the event that they are short-changed by their employer, they can present the data points offered by our tool to Singapore’s Tripartite Alliance for Dispute Management (TADM) or Ministry of Manpower (MOM),” he asserts.

Sojourner Brother will charge workers a monthly subscription fee to use their tool. Lum, a Nanyang Technological University (NTU) graduate, balks at accounts of workers being robbed of their rightful remuneration. He befriended migrant labourers while volunteering at non-governmental organisations. In the shadow of his retrenchment from a consulting firm in 2021, he reflected on the dislocating contrast between his job-hunting experience and that of his beleaguered migrant friends.

“While I had a lot of resources and platforms such as LinkedIn to empower my job search, I realised my friend had only one course of action, which was to find the agent and pay a high recruitment fee,” he elaborates.

Through the Singapore International Foundation’s Young Social Entrepreneurs programme, Lum won a $20,000 grant to fund his incipient platform. Aside from hacking away prohibitive, inflated recruitment fees — which may prevent injured or sick workers from seeking help, in fear of being sent home to rack and ruin — he wants to provide access to information and flexibility.

The app will feature tips on navigating Singapore’s byzantine regulatory system and cultural landscape, and may also incorporate an earned wage access (EWA) component. The latter is a growing trend; low-wage workers use apps to track their daily earnings and withdraw a portion on demand, before payday. Such solutions are gaining traction, owing in part to a wave of digitally savvy migrant workers who have transitioned to using smart phones over the pandemic.

Covid-19 appears to have been a double-edged sword. Lum cites Singapore’s Pre-Departure Preparatory Programme (PDPP) that sheds the need for migrant workers to book flight tickets via predatory agents in their home country, as a step in the right direction.

“The Covid outbreak has stimulated discussion of migrant workers’ living and working conditions and promoted certain reforms, notably in accommodation conditions, greater flexibility over changes of employer, more payment of salaries into bank accounts and improved pay for some workers. The constriction of new recruitment encourages employers to try harder to keep existing workers by treating them better and paying them more,” weighs in John Gee, vice-president of non-profit Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2).

A Mindset Shift

This bellwether of change is eagerly embraced by David Bensadon, who says that the current labour crunch — where demand outstrips the supply of helpers from overseas — is prompting agencies to lower transfer fees. Through automation, his employment agency We Are Caring circumvents the burdensome placement fees and salary loans typically foisted onto domestic helpers.

With their newly launched mobile app — created on the back of winning a DBS Foundation grant — potential employers can connect with domestic helpers locally and overseas. Employers sign up for free to view worker profiles and videos and can access their contact details for a $79 fee. Thereafter, they may set up an interview with the worker in their own time, beyond the agency’s remit.

“The mobile app allows us to scan and extract data from ID documents — underaged applicants are rejected — using Google Vision AI,” he shares. We Are Caring oversees the initial screening process and charges employers an administrative fee of S$1,169 for facilitating transfers.

The French national, who sold his apartment in Paris to bootstrap his business to the tune of S$100,000 six years ago, is a former advisor at the Ministry of Senior Citizens in France.

He says he empathises with migrant women saddled with heaving debt while trying to eke out a living to support their families. “Nobody wants to work in a maid agency. They want to be in a place where they can help people have better lives and have more sustainable relationships between employers and employees,” he avers.

The proverbial writing is on the wall. In MOM’s Employment Agencies Directory, We Are Caring scored higher than the industry average in terms of retention and transfer rate, as well as placement volume. Bensadon claims to have provided over 4,000 jobs to date. It’s a long haul from the company’s early days, where the entrepreneur rented a bed in a Little India Hostel to make ends meet.

As encouraging as ruddy accounts, is what Bensadon regards as an attitude shift enabled by technology. For instance, he says he no longer receives requests for helpers to relinquish their rest days, which his agency considers verboten.

“I think it is really positive how the younger generation tries to put themselves in others’ shoes, on top of being digital natives who look online to hire a helper. Digitalisation plays a role in cutting costs and increasing the quality of screening and efficiency, which pushes for a more ethical industry,” he notes.

Lum holds a similar view. “My sense from talking to employers is that 80 per cent of the construction company towkays (bosses) are younger than 50. The old guard has left and there are more young bosses who are familiar with digital solutions and want to get a leg up over their competitors via them,” he says.

Education First

But while technology has attenuated costs and paved the way for a more transparent, debt-free model, it’s hardly a panacea for social inequality. Ethical employment for migrant workers hinges on other structural variables such as upward mobility. According to Gee, TWC2 still encounters workers whose basic daily wage has stagnated at $18 for the past 18 years.

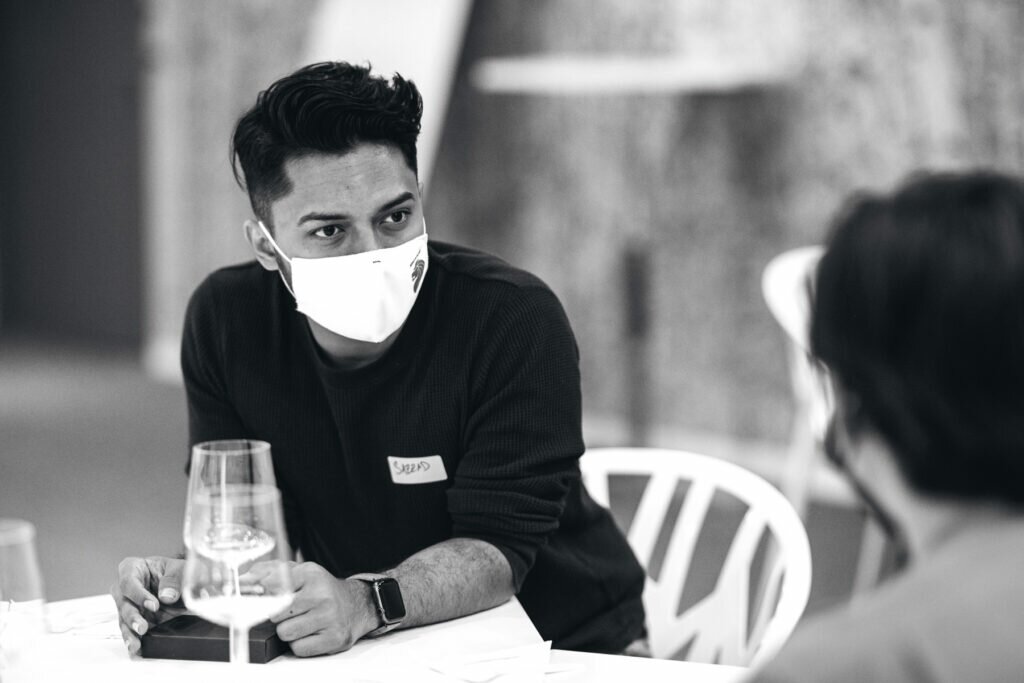

Sazzad Hossain never wants his migrant counterparts to feel ossified by their circumstances, usually impeded by a woolly understanding of their new surroundings. Having grappled with a foreign language as a new transplant who settled in Singapore with his family at age 11, the Bangladeshi started SDI Academy as a ground up initiative teaching migrant workers localised English from park benches.

“People with exceptional talent and skills miss out on opportunities because of the language barrier. When I interacted with migrant workers, I also realised that many of them could not even understand safety instructions, which endangers their lives,” he explains.

Today, the social enterprise he started as a junior college student offers migrant workers a suite of courses covering the English language, IT and computer literacy, as well as entrepreneurship. Over the pandemic, SDI extended scholarships sponsored by organisations for virtual courses in its mobile app. It’s also creating a Natural Language Processing (NLP)-driven tool that harnesses speech recognition technology to match workers to jobs without the use of resumes.

Rather than providing stopgap measures against exploitation, Sazzad wants his eight-year-old venture to be a “one-stop portal for migrants”. He says they’ve graduated 18,500 migrant workers since 2013, and plan to help 100,000 individuals in the next three years.

It’s no scattershot effort, if you consider the academy’s rousing alumni success stories. There’s Nazrul Islam, who was retrenched after helping to build the glistering Marina Bay Sands. He underwent upskilling and became a workplace safety officer. Or Faiz Ullah, promoted from general worker to assistant engineer at Keppel Marine after obtaining a diploma.

Perhaps most aptly summing up the migrant experience is Bangladeshi labourer turned designer Saiful Islam. Before a rapt TedX audience, he narrated his journey from debt-ridden high school dropout to empowered professional, in a delivery measured and tremulous with emotion at turns.

“Migrant workers are more than guys in yellow helmets and high visibility vests. Beneath all that, you and I are alike. I too have dreams, just like you. I too have ambition and drive. I too want to become the best possible version of myself,” he said.

Photography: Mun Kong

Grooming: Sha Shamsi using Chanel Beauty and KMS