The famous quote from Chuck Palahniuk in his novel Invisible Monsters goes, “Nothing of me is original. I am the combined effort of everyone I’ve ever known.” Judging by the amount of accusations dealt against luxury brands appearing on the regular, Palahniuk’s quote seems to ring truer more than ever.

Collectively, the industry-wide realization is that perhaps the concept of infinite creativity might have its limits after all. Given that the already-dwindling pool of new and original ideas are often exacerbated further due to globalisation, it seems like a herculean task to create anything new without adapting it from something that already exists, whilst juggling that with ensuring that designs are still commercially viable.

Typically, with fashion (or any creative process really), inspiration and references have always been a part of the progression or creation of an idea. In an ideal world, these visual references are usually heralded as a jumping point for an idea to grow, not as a resource for blatant adaptation.

But with the speed that consumers devour information, and their insatiable need for newness, copying and appropriating has also grown in tandem with the commercialization of fashion. It’s not just due to the lack of untapped original ideas, but also perhaps due to the pressure and creative standards that designers or brands feel they must live up to.

But for a generation who is this informed, and one that values authenticity and genuine ingenuity in the brands and tastemakers they align themselves with, unoriginality is not something that is taken lightly, especially when it comes to the stealing of another’s ideas.

According to a 2018 report done by Mckinsey, there are four core Gen Z behavioral traits, but they are all anchored in one major element — this generation’s search for the truth. The internet generation has grown up with vast amounts of information at their disposal, and are more pragmatic and analytical about their decisions. This in turn influences the way they view and consume brands. In fact, 76 – 81 percent of them are willing to drop a brand or company that showcases campaigns associated with gender stereotypes, racism or homophobia.

Mckinsey also reports that consumption becomes a means of self-expression — as opposed to buying or wearing brands to fit in with the norms of groups. Because of this association, if a brand contradicts its own values, it will be noticed. 80 percent of the group surveyed said they refused to buy goods from a company involved in scandals, with 65 percent saying they try to learn about the origins of anything they buy.

Younger consumers now demand full transparency, and have no issues calling out alleged perpetrators when they smell foul play.

While holding bigger industry powers accountable and keeping power balances in check can be noble, originality is also subjective to the person viewing it.

What one man considers “original” could be an oft-used idea from another – just look to Balenciaga’s quirky-shaped bags derived from familiar Asian everyday vignettes that were lauded by the Western world.

And whether guilty or not, once a designer or brand has been tried in the court of public opinion, sometimes it can be tough to regain the trust it has lost with its consumers.

When Borrowing Inspiration Crosses The Line

Take the most recent incident with Virgil Abloh, CEO and founder of his label Off-White, and artistic director of Louis Vuitton’s menswear arm. Abloh, a post modernist who uses appropriation as the basis of his practice, is no stranger to sensational media headlines, due to his views on design philosophy (he believes 3% is all you have to change to make something new), high profile friendships (he is Kanye West’s creative director and BFF) and frequent call outs by his industry peers for allegedly copying (or should we say “COPY”) their designs.

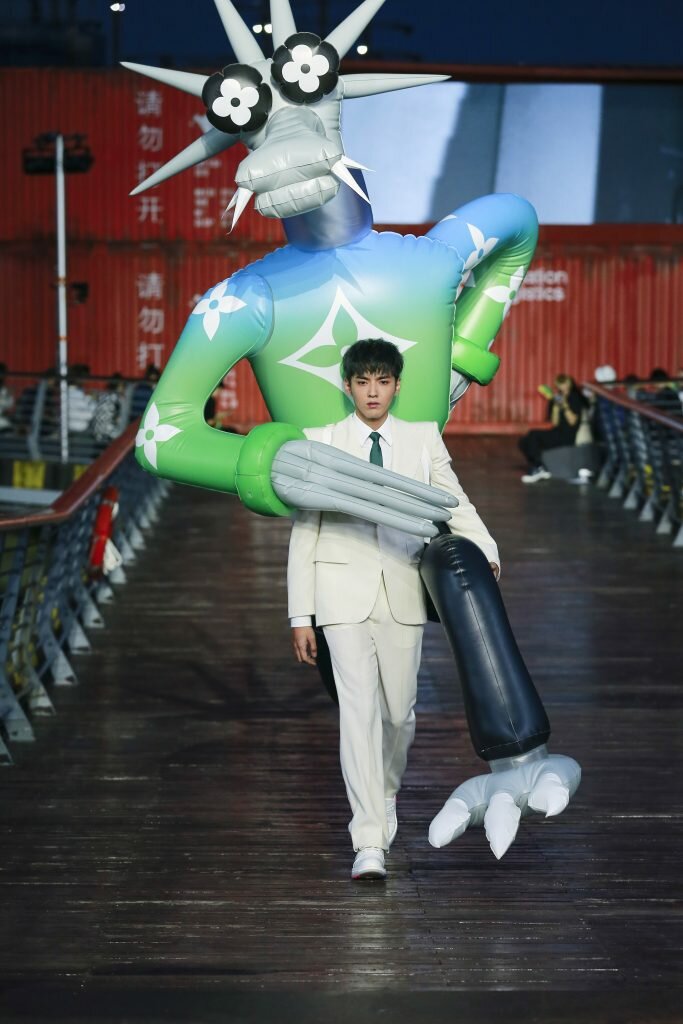

The latest in this line of accusers is Antwerp Six member Walter Van Beirendonck. The Belgian designer furiously accused Abloh of plagiarism due to similarities he saw in Abloh’s latest SS21 menswear collection for Louis Vuitton with his own AW16 and AW18 menswear collections. The design elements he took issues with? Colourful asymmetrical eyewear, stitched-on plushies and oversized and deconstructed tailoring.

-

Image: Louis Vuitton -

Image: Louis Vuitton

While Van Beirendonck himself did acknowledge that borrowing inspiration from other designers is common practice, he felt that Abloh had crossed the line. In a statement he gave to Belgian magazine Knack Weekend, Van Beirendonck said, “Copying is nothing new. It’s part of fashion. But not like this. Not on that level, with their budgets, their teams, their possibilities. That’s what is shocking to me”.

For Abloh, this stung (he called the comments “hate-filled”), as the designer has continually been lambasted in the press by his lack of innovation by industry peers, including one by his fashion hero Raf Simons.

Representatives for Louis Vuitton and Abloh have both denied Van Beirendonck’s claims, citing a specific Louis Vuitton SS05 menswear show with models clutching teddy bears as the inspiration for his collection. While there were no direct mentions of that specific show from 2005, the show notes did explore Abloh’s disparate influences in painstaking detail and spoke about the “the upcycling of ideas”, perhaps to be seen as a nod to the French house’s SS05 collection.

And while the design details are uncannily similar, who’s to say who is right or wrong in this situation? Van Beirendonck, while critically acclaimed, has had less commercial success than Abloh has enjoyed. So, it can be disheartening to see similar ideas receive accolades when done on a more visible platform.

In defending his work, Abloh displayed the evidence for his work, though not everyone (including Van Beirendonck) is fully satisfied with his explanation. If one is to come from the viewpoint that Abloh was indeed inspired by a collection in particular from the house’s repertoire, should his team and him have done more research to avoid this mess? And if their research did turn up Van Beirendonck’s preceding work, would it have worked better if Louis Vuitton collaborated with Van Beirendonck himself?

Who Does An Idea Belong To Once It’s Already Out?

While there are merits to call out culture, especially when due credit needs to be given, who owns an idea once it’s made public? Just how different can our perspectives be if we are all exposed to the same things globally? And what if all this visibility and exposure are blending all our ideas into one? Do you get to claim an idea if you’re the first to conceive it, or the first to popularise it commercially?

Therein lies the problem when it came to Vietnamese artist Tra My Nguen, and her own tussle with Balenciaga.

In July, Nguyen called out Balenciaga for appropriating her project—a motorbike wrapped and collaged in clothing to create “wearable sculptures”—and replicating it almost exactly to a tee for a social media campaign image. Nguyen’s project sought to explore Vietnam’s female motorbike culture and she took inspiration from her own family history where her mother sold her bike in order to raise funds to immigrate to Germany.

While Balenciaga was quick to deny the claims and cited their own research, the fact that in June 2019, a Balenciaga creative development strategist had met Ngyuen (then a student at the Berlin University of Arts) during her master’s presentation and solicited for Nguyen’s portfolio felt coincidental at best.

Furthermore, the same team member got in touch with Nguyen again in October 2019 for more images of her portfolio, citing that the ready-to-wear team was looking for interns. After Nguyen replied with multiple process images, she never heard from Balenciaga again.

In a statement posted on their Instagram stories timeline, Balenciaga claimed that the image was “not based on the work of any artist” and “was inspired by how street vendors sometimes display their merchandise”. They followed this up with a series of inspiration images featuring cars covered in clothing and fabric and included additional images from the shoot, showing a car and a tractor covered in clothing. Balenciaga also doubled down on their statement, citing that their recruitment and social media teams “do not share talent information,” and that it will “work to better follow up with applicants regarding the status of submissions going forward.”

Are Our Influences Just An Amalgamation Of Everything We Know?

So is the internet and globalisation really to blame when it comes to the lack of innovation? Are we really all producing similar ideas due to the references and cultures that we’ve been exposed to?

This calls to mind a popular social experiment once done by Derren Brown, where the mentalist used subliminal messaging to influence two advertising agency creatives to come up with ideas that were nearly identical to his, even if they were not discussed beforehand.

How did Brown manage to pull off the stunt? By constantly exposing the pair to images that reflected Brown’s vision during a 20-minute cab ride. And while this was a controlled experiment, it demonstrates just how effective seeing the same imagery can affect our points of view, and how they might not be as unique as we think after all.

So if we as a society can’t exactly control what we see in the world, how can fashion brands do better to stay at the forefront of originality? For starters, employing a research team to ensure that due diligence is being observed. Not only would the research be useful in providing verification of a designer’s collection, this could help luxury houses discover lesser known talent, and help cultivate a creative community with an influx of new in-house talent and ideas.

While no luxury house has publicly announced such a community as of yet, there has been strides to cultivate new talent within the industry. Just think of Gucci’s willingness to collaborate with lesser known artists such as Coco Capitan or Guccighost that benefited both artists and the brand after working together.

Other luxury houses have also found their own ways of cultivating creativity such as Loewe’s annual Craft Prize and French conglomerate LVMH’s LVMH Prize For Young Designers where past winners have included Jaquemus and Marine Serre.

And, in the off-chance that a brand is guilty and rightfully called out, what is the best way of dealing with this? By holding themselves accountable and making amends. In a scenario where everyone wins, Gucci did the right thing when they were accused of appropriating a mutton-sleeve logo jacket created by Harlem tailor Daniel Day, better known as Dapper Dan. The tailor, who was put out of business in the ’90s by the fashion brand due to copyright infringement, took to social media to set the brand straight.