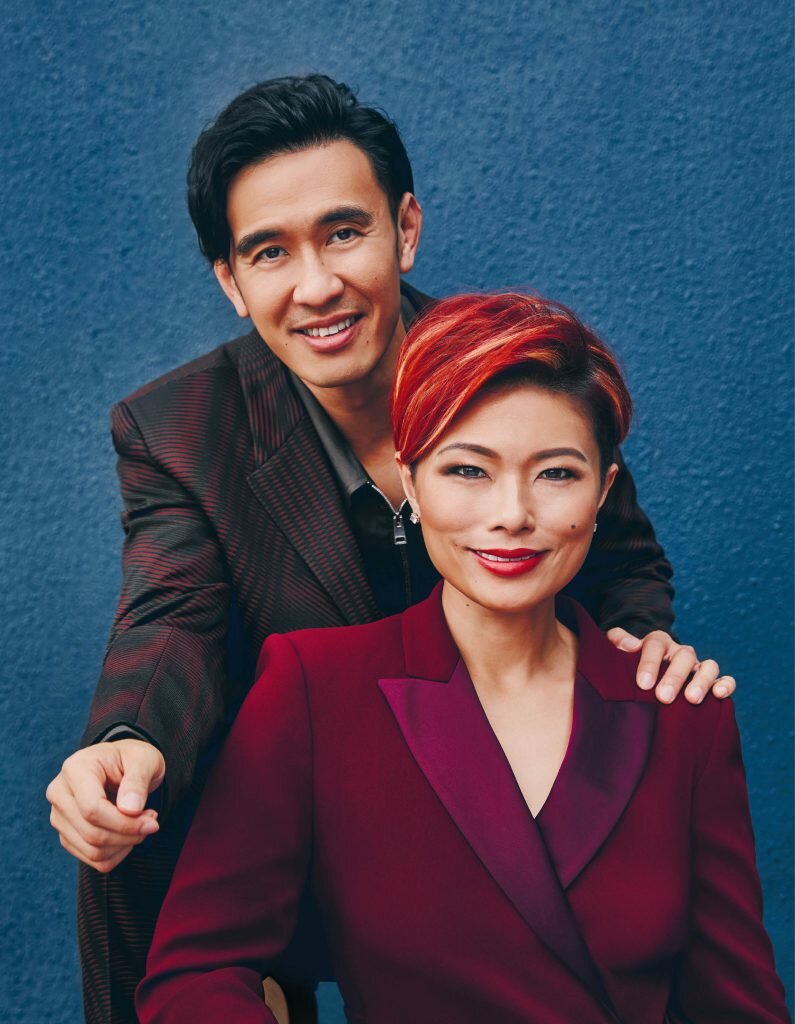

There is a distinct cinematic quality to the story of siblings Nichol and Nicholas Ng’s family — a thoroughly dramatic arc spanning three generations that’s laced with heartbreak, pathos, financial collapse, a world war, resilience, cliffhangers, liberal doses of chutzpah and, because this is a movie, a triumphant comeback against all the odds by the attractive leads. In fact, there’s enough material here for a 10-episode miniseries. Will someone please page Netflix?

In most dramatic family biopics, the centrepiece — the lynchpin for the narrative — is the business, invariably something sexy involving lots of private jets, MacMansions and outré designer outfits. In Dallas, Dynasty and All the Money in the World, it’s oil wells. In Billions, it’s hedge funds. In the case of Nichol and Nicholas Ng’s family, however, it’s the decidedly anticlimactic food services industry, albeit one that’s raked in a healthy $60 million annual turnover since they reinvented the family business in 2007.

And here’s where reality peels away a little from celluloid fantasy — not too much, but just enough for you to realise the real world stakes, both emotional and financial, that are at play here.

“I was at home the day the banks came to seize our house in 1997,” Nichol says. “They gave us 30 minutes to pack up and clear out. I was 19. After that, we just lived in one rented home after the other. I didn’t own my own home till I married and I managed to buy a house with my husband’s money and my CPF.”

It was a fall from grace no one saw coming. Well, at least not Nichol and her younger-by-a-year brother Nicholas, who admits their parents sheltered them from a lot of the financial turmoil roiling around them at the time.

Of course, hindsight is an implacable judge but for a while there, things really were rosy, a rags-to-riches tale in the best traditions of its genre.

The Ngs’ paternal grandfather Ng Lim Song left his native Swatow in China’s Guangdong province in 1934 with his first daughter to start a new life in Singapore, and in 1939 started a provision business named Ng Chye Mong. After the death of his wife, he remarried and had nine children with his second wife — Nichol and Nicholas’ father was the eighth born.

Figuring that it made more sense to work on a multiplier effect rather than toil on a small standalone business, grandpa Ng hit on the idea of food distribution. Run out of a shophouse in Rochor, he sold groceries and ducks, braised Teochew-style, to the colony’s hawkers and businesses.

By the early 1980s, Ng’s enterprising children had diversified the family business into seafood and cigarette trading, and even a duty-free shop in the Maldives. He died in 1977, but he had raised extremely competent children. At its peak, the family business operated in 25 countries and by the 1990s, it was raking in an impressive turnover of US$250 million ($340.2 million).

It’s no surprise to learn that Nichol and Nicholas grew up comfortably. Their father had an office in Orchard Road. On weekends, there were retail expeditions to Louis Vuitton at the Hilton. But even then, in the midst of this glossy upper-middle-class upbringing, an unexpected cold-eyed, sober streak ran through the Ng children.

“I saw how hard my father worked,” Nichol now says, “but we over-expanded.”

“And I was quite stingy,” Nicholas chimes in with a laugh. One thing you notice about the siblings is that they laugh a lot. All the time. “I would chase my mum for 20 cents. We kept our heads down and worked hard. It didn’t matter if we had money or not, we worked just as hard.”

Their mother, an active member with the Lions Clubs of Singapore, brought her young children along on visits to old folks’ homes. Though Nicholas avers to never having any obvious passion for charity, something must have stuck because decades later, he and his sister would set up Singapore’s first — and to date, only — food bank.

Meanwhile, the 1997 financial crisis took no prisoners as it cast its net far and wide. When it landed over the Ng family home with a 30-minute pack-and- go order, Nichol’s father scrambled and managed to buy a week’s grace. “Overnight, we lost everything — the house, the car. We left everything behind.”

Even the family office and warehouse were reposssessed. The only thing that was salvaged was the original food distribution business set up by her grandfather which was being run by two of her elderly uncles. “We managed to ringfence that one asset. We lost the rest.”

Nicholas was at the time away in boarding school in Ballarat, Australia. He never saw the family home again and when he returned for the holidays, he stayed with his grandmother. “My sister laid it all out for me. We had multiple conversations when I was home. And because IDD calls were so expensive, we wrote long letters on foolscap paper. This was before ICQ! Does anyone even remember ICQ?”, he says with a laugh. It washes away what must have been years of anxiety and privation.

One year at a time, the family regrouped. Nichol continued with her schooling, waitressing for extra pocket money and eventually graduating from the National University of Singapore with majors in economics and Japanese studies.

Her father still threw her a 21st birthday party even though there was no money. He was already paying her school fees with his CPF. “He felt a sense of shame. I saw that guilt,” she says. “But my attitude was that as long as the family is together, nothing matters.”

Nothing matters, and she means that literally. Not Sars, and not even the 2008 global financial crisis that roiled the economy.

After a stint in the marketing department at MediaCorp, Nichol, at her father’s request, joined the family business in 2002. At 24, she was the youngest employee in a company peppered with elderly men. She rolled up her sleeves and got to work digitising the business, all the while thinking of ways to update a company that was, at the time, still being run in a very traditional way.

Inspired by London’s legendary New Covent Garden Market, she recognised that her grandfather’s business, fusty as it was, still had strong legs. Even in the worst of times, people needed to eat, so if nothing else, a food distribution company is a recession-proof rice bowl.

In 2007, she bit the bullet and made a formal offer to buy the family business. “We had zero bank financing and we bought it with an arms- length valuation just so that it could be run without any interference from other family members.”

The first order of business was to rename the company, in favour of something more millennial and relatable. “We had intense discussions about this,” Nichol remembers. “We wanted to continue the heritage, but not necessarily the name. We needed something funky that reflected the food business. We felt ‘X’ was an all-encompassing symbol. So we came up with FoodXervices. And we changed the corporate colour from clean white to black. People thought we’d been bought over by an American company!”

A year later, Nicholas cashed in his Simon Fraser university degree and five years at Tiger Beer to join his sister at the helm at the newly-minted FoodXervices.

Over the years, the pair have developed the business into a comprehensive one-stop food shopping and distribution service that is a juiced-up, digitised beta release of their grandfather’s original model with nearly 200 staff and an enviable Rolodex of 5,000-odd clients including Accor hotel group and Shake Shack.

“We’ve revamped our grandfather’s company and given it a new lease of life,” Nichol says brightly. “The magic is that we are a start-up with an 80-year-old body.”

Significantly, the demographics of the staff have shifted as fresh blood is recruited, with Nichol zeroing in on candidates of a similar age, academic bent and drive. “There is sometimes a lack of creativity and resilience among the current generation because things have been so comfortable. They don’t ask enough hard questions, but they have the heart for things that may not matter to some of the earlier generations, like the environment and sustainability. So it’s about combining their love for these issues with the strength, experience and knowledge of earlier generations. I think that will be such a powerful combination.”

It’s not quite a scene out of Cocoon, but the same positive sense of invigoration, rediscovery and unbounded possibilities filters through and colours everything.

In 2012, the siblings set up a charitable arm to their business. Food Bank Singapore is a physical and virtual catchment of food donated by farms, manufacturers, supermarkets, consumers and the like. These are parcelled out to a network of some 360 charities, non-profits and community services such as the Salvation Army and Willing Hearts. Collectively, the food, which would otherwise have been thrown out, feeds some 250,000 Singaporeans.

For Nichol and Nicholas, the synergies between Food Bank andFoodXervices are obvious. “We wanted to do something that was close to our hearts and we decided early on that it should be food-related,” Nicholas says.

“People thought we were crazy,” adds Nichol. Again, that easy laugh. “We were already spending so much time together in the office and now we were doing a charity together!”

Of course, it’s easy to play couch therapist and draw a line between Food Bank’s mission to fight food insecurity, and the siblings’ own early adult privations and financial insecurity. Certainly, their conversations are peppered with references to the community, working families and the underprivileged. Food Bank, Nichol points out, emerged from a gap in the system and “not because our family’s foundation was looking for something to invest in. We were ourselves struggling in 2012 to reinvent ourselves into a more modern business, but we were also mindful that some others struggled to even put food on the table.”

Their decision to build Xpace manifests this awareness with a sharper focus. On paper, this sprawling 250,000-sq-ft, eight-storey complex in Pandan Loop — designed by architects and designers P&T Group and Space Matrix — is a hybrid of co-working and lab space, resource centre and incubator for restaurateurs and F&B start-ups and companies.

Conceived before Covid-19 turned the world upside down, the fallout of the global shut-down of businesses, especially in the F&B industry, has recast Xpace’s mission in a subtle but crucial way. With its communal resources, adaptable test kitchens and production spaces, showrooms, chillers and freezer storage for 10,000 pallets of food, alongside sales support, delivery trucks, and matchmaking services, it is both a fully-serviced base for established businesses looking to cut overheads and new overseas ventures looking to establish a beachhead in Singapore; and a lifeline for neophyte chefs and small-scale businesses to brainstorm and workshop from ghost kitchens, freed from the tyranny of locked-in rent agreements and the relentless pressure of running a bricks-and-mortar operation.

“We want this place to be like 1960s’ Silicon Valley,” Nichol explains. “A community that shares ideas and resources, where no one works traditionally. And we want to be a better business partner than we are a landlord.”

Xpace is also the new permanent home for FoodXervices. After 13 years of increasingly cramped rented space, “we really needed our own long-term place, one built to our own specs and with no landlord.”

But it’s the less visible touches that showcase the thoughtfulness and generosity of the siblings’ corporate vision and managerial style, not least the staff gym, cafeteria, and nursing and childminding services.

“These things don’t cost much, but it’s what we would like to see in a workplace and it’s something the staff appreciate,” says Nicholas. “Besides, we want people to have fun here. It’s not your typical stuffy SME.”

And still, there is a touch of regret. The shade of their father, who died in 2016, hovers lightly. Moving into Xpace, says Nichol, has been both surreal and emotional. “By having our own building, the business has come full circle. I’m sad he never got to see this.”

The sentimental moment passes and her tone shifts briskly, because there is still plenty to be done. Accenting the undercurrent of food insecurity in Singapore, Covid-19 has created a new sense of urgency for the Food Bank’s resources. The days are packed, especially when you factor in Nichol’s four young children, and Nicholas’ two, all of them aged under nine.

“But we actually like the business,” he says. “My sister and I work well together as we’re always looking out for each other. And we talk through a problem even though we may end up agreeing to disagree. We never ever avoid it or sweep it under the rug and hope it disappears.”

As family dramas go, it’s not terribly exciting, but we suspect the Ng siblings have had enough drama to last them a lifetime. At least till season two anyway.

This feature first appeared as the cover story of the November 2020 issue of A Magazine.