With the calls for social distancing in recent months, certain hobbies, once left by the wayside, are regaining prominence. Books are being consumed like Michelin-starred dinners, puzzles are as popular as Korean dramas, and esoteric efforts that hark back to Jane Austen’s days, whether it’s needlepoint or calligraphy, are making a comeback.

Welcome to the slow life. But is this a short-term reset brought on by the needs of the Covid-19 pandemic, or could it end up sparking a fond return to days of yore?

With 13 years as a ceramicist under her belt, co-founder of Mud Rock Michelle Lim has become something of a craft activist in the industry. The way she sees it, we are in the midst of this century’s third craft renaissance, kickstarted in the throes of the last major global economic crisis.

“In Singapore, when I went to school, our arts textbook was named Arts and Crafts. After the ’90s, it stopped — people actually felt it wasn’t cool to be associated with craft. ‘We want to be associated with art and high art’,” she says.

-

(Image: Mudrock Ceramics) -

(Image: Mudrock Ceramics)

“Then you had the economic recession in 2008 together with the rise of social media. Things like Etsy, Instagram… all that started to come together around the time Lehman Brothers brought down Wall Street. That’s when people slowed down and started the slow food movement; they did more yoga and everything related to self-improvement.”

As people lost jobs, they turned to passion projects, and some passion projects became careers.

“Then people forgot the reason we went back into craft, because life went back to normal,” Lim says.

Today, besides running a thriving ceramics business that does private commissions, retail and workshops, Lim also proselytises the craft cause — she’s given a Ted Talk on the revival of dragon kiln pottery, and she and partner Ng Seok Har go so far as to price their wares politically. While she says it’s common to find a hand-fired mug going for $70 or more at a fair, Mud Rock sells its Dino mug for $38.

“It’s important to educate each other, not to bring prices up because it’s a hot thing but to keep it affordable, so it’s not just a trend the rich can afford,” she says.

At Mudrock workshops, hobbyists don’t just learn basic pottery, they also learn that the sexy part — where Patrick Swayze’s character embraces Demi Moore — is only the beginning; and Lim is used to seeing the crestfallen faces of students when they realise they can’t take their wares home right after class. Clients and students alike must be educated that “clay is organic, it requires the atmosphere for air to dry, water to evaporate…”, Lim says with a laugh.

Education is also what Yama Chan seeks to achieve with Crafts on Peel, a newly opened craft museum in Hong Kong. It showcases crafts that are specific to the city’s unique culture, from guangcai porcelain to making birdcages or dim sum steamers — arts that are losing prominence because they are too ancient and, in some ways, too random. The next generation may not want to be forced into achieving mastery and hobbyists may not have ready access to such forgotten endeavours — fifth-generation makers of bamboo steamers aren’t exactly known for their raging social media influence or their willingness to take on casual summer interns.

For its inaugural exhibition, Chan invited young local designers to collaborate with craftspeople to create contemporary translations of the art form. For instance, pairing the maker of lion heads for lion dances with a papier-mache artist-fashion designer. Crafts on Peel also hosts workshops on occasion, with a recent one featuring bamboo weaving.

-

Liberty of the Wind displayed at Crafts on Peel

(Image: Crafts on Peel) -

Go Out with Guangcai

was one of the works on display at Crafts on Peel’s inaugural exhibition, where Chan invited designers to collaborate with craftspeople

(Image: Crafts on Peel)

It’s important to preserve these techniques in a world driven by social media algorithms that create an endless loop of interest in trending topics while leaving others completely in the cold. Providing new context for the traditional is essential in extending their relevance as well as to ignite interest in their original appeal.

“As our lives become more digitised, I treasure more and more things that are handmade,” says Chan. “When an object is made by hand, it brings an emotional connection; when an object is made with traditional techniques, it perpetuates the stories and traditions embedded in the process of making them.

“When traditional crafts find modern purposes in our daily lives, we are reminded as we use these objects, of the emotional connection, the stories and traditions carried in them. I believe traditional techniques provide a cultural language for contemporary designers to express themselves in a unique way.”

-

Reborn Merman

(Image: Crafts on Peel) -

Reborn Merman

(Image: Crafts on Peel)

Lim supports this theory, although the field of ceramics seems to be extremely on-trend these days.

“How many $70 mugs can you buy? Will you use it every day? It’s so much more precious because it’s $70, and you might lose that daily relationship you have with an object from using it every day,” she says.

“We shoot ourselves in the foot every time we say that handmade mugs and factory mugs are the same, [but it’s true and] it’s the only way we can move society forward. If you think the value of something is lower because it’s factory-made, that’s saying the factory worker’s value is lower than mine. We started Mudrock to go against that. You don’t buy from us because our value is higher than the factory workers’, but to say no to the big guys.”

“I don’t mean to politicise this but it is about the empowerment of the craftsperson. Factory-made is handmade too. Factory workers are human. The difference is, I have autonomy, I have privilege. We support the local [crafts]person because we are saying no to capitalism.”

This anti-establishment mindset that marks the millennial generation, coupled with the ability for empowerment through digital channels, can also be thanked for the growth of craft beyond just being a hobby — the availability of social media as an outlet and marketing tool combined with a culture tolerant and even encouraging of later-stage career change, “slashie” lifestyles and entrepreneurial spirit.

-

Yama Chan, founder of Crafts on Peel

(Image: Crafts on Peel) -

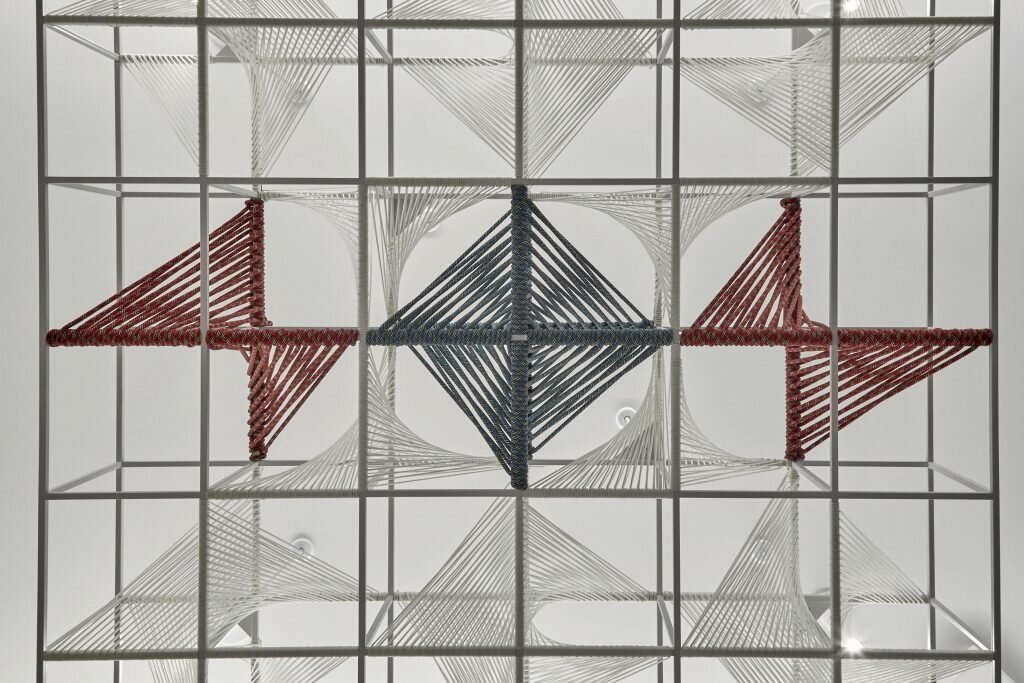

Windy Chien

(Image: Windy Chien)

Windy Chien, for example, is a California-based artist-craftsperson who ran a record store for 14 years, then worked at Apple for iTunes and its App Store for close to a decade. When she took time off, she rediscovered the childhood pleasures of macrame and decided to engage in a personal project which she called The Year of Knots, where she learnt a new knot daily for a year and documented it on IG (it’s now also a book); the first edition of the project was acquired by Facebook for its offices. Chien now works full-time as a rope artist, creating striking installations clearly influenced by her earlier careers.

“From the record store I worked at for 14 years, I learnt it’s all art and it’s all valid,” Chien says. “What’s required is close listening and close looking, and a respect for process or concept. Intent is often a factor, but not always: One of our best selling albums was by the Thai Elephant Orchestra, a group of up to 14 elephants who spontaneously made ‘music’ when given instruments… another of our bestsellers was a four-CD set of recordings of Cold War-era numbers stations, mysterious radio transmissions consisting entirely of human voice–recited series of numbers and understood today to be coded communications among spies.”

Similarly, when Chien is in the “flow” in her studio, the rope and knots very much dictate the direction of her work.

The advent of digitalisation hasn’t just been a tool either — for example, one rope hanging by Chien is very clearly and literally inspired by circuit boards.

(Image: Windy Chien)

“[But also] at Apple, I fully absorbed the lessons of simplicity and stripping away of decorative elements. As legendary designer Dieter Rams pointed out, good design is ‘as little design as possible’. By removing the merely decorative and unnecessary elements of a design, the purity of the object shines through. The essence of the object is also where its beauty lies. Apple products exemplify these principles. Similarly, in my own work, I abhor the decorative and remove any element that does not contribute to the overall meaning and impact of the work,” she says.

Inasmuch as the digital world can empower the individual, there are pitfalls too — because of Pinterest and IG, DIY techniques have been demystified and it’s all too easy for a newcomer to be seduced by influencer fads or worse, to respect crowd-pleasing visual language over true individuality.

“People will ask, ‘Can we do the thing where you blow bubbles and it becomes the glaze?’,” says Lim of Mud Rock. “One guy does it, he has a lot of followers, and everyone wants to do the same thing. I show them but I say that’s not my aesthetic.

I understand you want to learn, nonetheless. If you want to see it in a positive light, it’s great they’re all trying this but they’re also not finding their own style.”

“We do have studios copying us too. But the good thing is, all the recipes are unique to us. You can follow the form but you don’t know what I put in my glaze for it to come out the same colour. As long as we rely on ourselves, we are protected by that. People want you to share; the old me would love to but we can’t be so naive. It’s hard to explain to those who don’t make a living doing it. It’s crucial to protect.”

-

(Image: Windy Chien) -

(Image: Windy Chien)

In the end, craft — whether you call it bespoke, artisanal, DIY or handmade — has power at its root. For the artist, it is the power to express language and a personal point of view through creation. For the hobbyist, it is the basic capability of creating something with your own two hands. For the consumer, buying craft is about empowerment.

“You look at this virus; people are buying these things that are unnecessary because spending power is the only power they have now. They feel powerless, but at least they can buy toilet paper,” says Lim. “[What we do] won’t be a ‘trend’ unless we continue to educate people who support us.”

This story first appeared in the May 2020 issue of A Magazine.