The old and arduous way can be romantic. But in an era of technology and mass production, it is time-consuming and cost inefficient. That’s why luxury conglomerates talk a big game about heritage and all the ways they help keep rare handcrafts alive. But they’re not the only ones fighting the good fight. We meet three designers who have been quietly but diligently safeguarding their centuries-old legacies and traditions.

Monmaya

Of the many design trends humanity has enjoyed over centuries, minimalism arguably has the most staying power. In an increasingly noisy world, stripping things down seems to be the most popular way to perceive beauty. But it can get boring.

Extravagant details and embellishments are the delightful calling cards of old world luxury and we should not dismiss them in the name of decluttering. At Monmaya, it can take over a month to make one Sendai tansu — highly ornamented chests favoured by samurai and royalty that originated in the 15th century.

“Three weeks for woodworking, three months for painting, followed by one week for the metal fittings,” explains Kazuhiro Monma, the company’s seventh generation successor.

These tansu from Sendai are prized for a reason. The front panel uses zelkova and the interiors employ paulownia and cedar. These materials are excellent for controlling humidity.

A lacquer technique known as kijiro-nuri helps the artisans achieve a mirror finish on the wood, but “it is a very advanced technique used only for Sendai tansu, and it involves over 30 processes,” states Monma. “Not a single speck of dust is allowed.” Finally, the metal fittings are decorated with elaborate three-dimensional patterns of dragons, peonies and other auspicious motifs.

Monmaya also offers restoration services. The oldest one it has come across is a 150-year-old chest. While many of their traditional tansu look like they were lifted out of the Edo period, Monmaya has had to develop with the times to stay relevant.

When the economy was growing, it made larger chests to accommodate more things. When more compact Western-style clothes took over kimonos, chests became smaller. Recently, Monmaya collaborated with designers for smaller, more contemporary items under the Monmaya+ label.

Monmaya is flourishing. It opened its first store outside of Japan in Hong Kong in 2018, followed by another in Shanghai a year later. But it still struggles to find young artisans to impart this knowledge to. “I would like to preserve our skills and pass on the culture of Sendai tansu to the next generation,” he muses. “After all, our products are sold in other countries, proving that the world accepts it. It is my proudest achievement.”

Gato Mikio Shouten

During Japan’s bubble economy period in the 1980s, demand for Yamanaka lacquerware exploded. The Yamanaka hot spring area in Ishikawa Prefecture’s Kaga City became famous thanks to its exquisitely hand-carved wooden pieces coated in lustrous lacquer. The craft originated around 400 years ago by woodworkers who settled in the nearby mountains.

Unsurprisingly, the laborious craft couldn’t keep up with the demand. Many companies had to switch to plastic and used manufacturers in China. While pretty to look at, these attempts are a far cry from the real deal.

Masayuki Gato of Gato Mikio Shoten and his forebears have no interest in massive sales figures. Founded in 1908 as a woodworking plant, the company has maintained its focus on bringing out the beauty of domestic wood — with or without lacquer.

“In my father’s day, the best-selling products were snack bowls placed on kotatsu (Japanese heated low tables) to hold tangerines and rice crackers. Such products now are usually tacky,” he quips.

“Not that the third generation was tacky. It’s just that they updated what they inherited from the previous generation with the current trends of the world, otherwise traditional crafts would have fallen into disuse. I am not making fun of my father’s products. But I am making products that meet the demands of the times.”

Indeed, the cups, bowls and tableware that Gato Mikio Shoten is producing today are breathtaking. They show off the wood’s natural grain or the decorative skill of the woodworker.

The company even sells wooden wine goblets, which imitate the fine stems and thin-lipped forms of crystal drink ware perfectly. It achieves this by vertical wood-turning, a signature technique of Yamanaka lacquerware artisans. Even something as simple as a tea canister feels luxurious thanks to the uniform grooves carved into the wood.

“In the past, artisans would compete to show off their skills in kashoku-biki, or decorative grinding. The most skilled ones could make eight stripes in one millimetre.”

Unfortunately, these skills are becoming increasingly scarce. Many are using tools made in the 1960s that contain parts that are no longer being manufactured. The artisans also cannot afford to pay apprentices. Gato reveals that simulations have forecasted that the number of woodworkers making Yamanaka lacquerware will halve in 10 to 20 years.

But he is determined to keep this precious knowledge alive. He plans to build a new factory this year and invest tens of millions of yen into new machines.

Mikio is the leader the craft needs. “When I opened a directly managed store four years ago, I became disappointed and annoyed when visitors to the hot springs would leave with the impression that Yamanaka lacquerware is a cheap souvenir,” he says.

“Therefore, I opened [online store] Gatomikio/1 — not just to sell products but to return to my roots. Each customer can learn about and take home the stories that only Yamanaka lacquerware can tell.”

Duyiyao

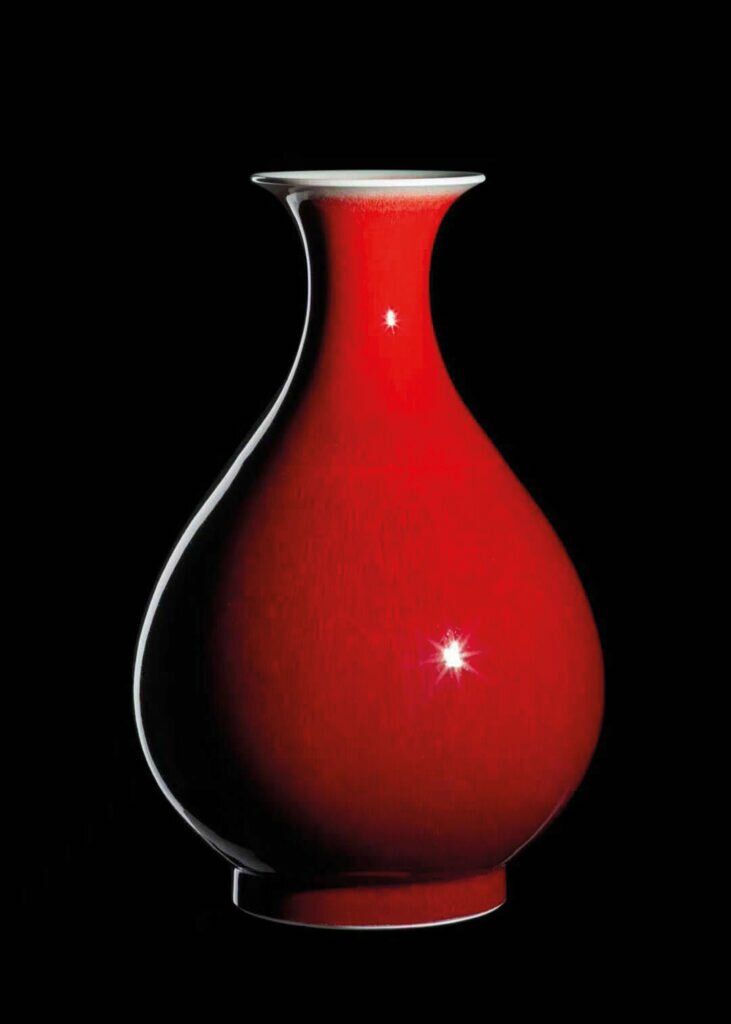

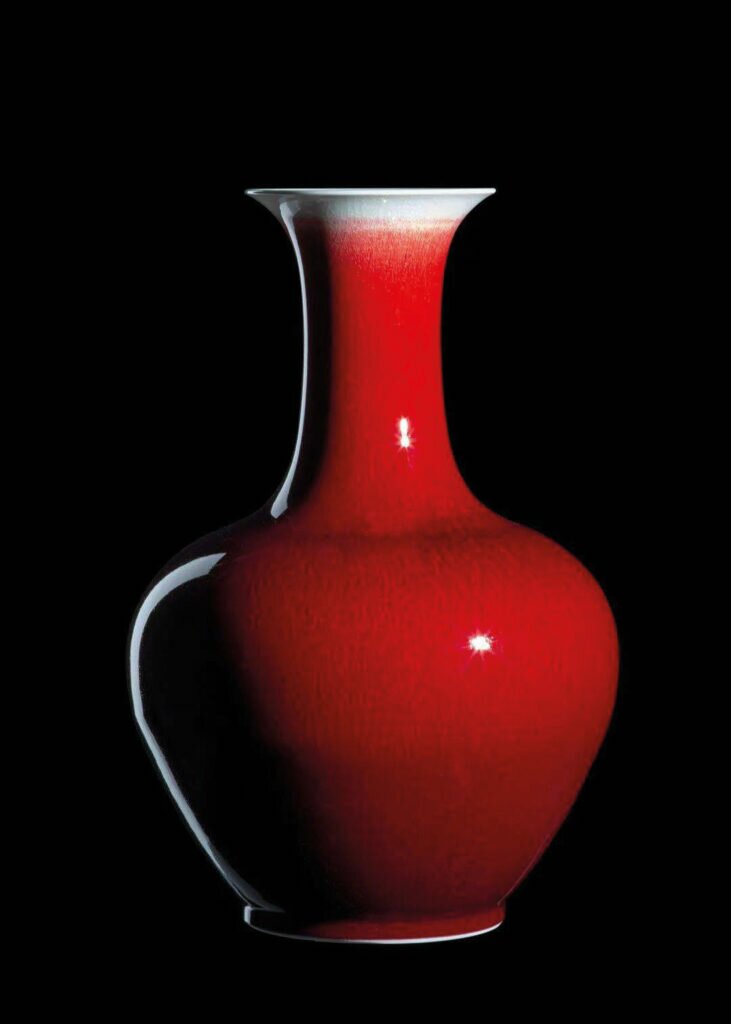

Growing up in the porcelain capital of the world, with a family that’s been in the ceramics business for centuries, it’s hard to imagine steering one’s career away from the craft that made “china” synonymous with porcelain. Not that Shuchang Liu minded. “I grew up surrounded by this atmosphere of craftsmanship. It was such a joy,” shares the Jingdezhen-based founder of Duyiyao.

He continues to feel this joy as a full-fledged ceramist after completing his apprenticeship with his uncle. Duyiyao’s porcelain wares have dramatic, elegant hues. Their deep and expressive glaze reflects their Jingdezhen pedigree.

But it’s not enough for Liu. “I am inexplicably moved every time I complete a piece of work. After that, I immediately spot what improvements I can make and start thinking about my next goal,” he reveals.

Perfectionism is a characteristic that artisans at the top of their game share. That unwillingness to settle keeps them going through the monotony of repeated actions and failures.

“Ceramics is a process that involves multiple crafts and techniques, so you may spend your whole life on a single process and think about how to make it better,” he agrees. “I have kilned more than a thousand times. But I still feel there can be endless iterations — the possibilities are infinite!”

Liu specialises in the raw materials and firing processes, so many of his goals correspond to improving those skills. These include understanding the principles of colour development in copper-red glazes, or better comprehending how colours transcend during the firing of sodium silicate, a material used to achieve a deliberately cracked texture in porcelain.

His most ambitious goal, however, is to recreate the legendary Yohen Tenmmoku bowls and their surreal, galaxy-like patterns. Originally made in China, there are only three fully intact bowls in existence. All three are currently in Japan.

“Traditional Chinese ceramics have a long history. The different periods present different preferences and techniques, which is why ceramics are the best carriers of Chinese culture.”

These three labels are available on Vermillion Lifestyle, an international online marketplace that gathers the best Asian heritage designers onto one centralised platform.