Ken Koh might have taken over his family’s soy sauce business just a few years ago in 2017, but the man has already earned himself a reputation as a trailblazer in the industry.

From opening a boutique store on East Coast Road to holding soy sauce appreciation classes to positioning his family’s umami-packed produce as an affordable luxury item for connoisseurs, the 37-year-old has emphatically reversed the flagging fortunes of Nanyang Sauce and turned it into a beacon of hope and inspiration for similar heritage companies.

But out of all his innovative marketing strategies, it is his latest that will take the brand to new heights – literally.

Located more than 2,000 metres above sea level in the Land of the Thunder Dragon, the brand’s latest outpost in Bhutan is set to be the highest soy sauce brewery in the world when it opens in mid-2022.

But Koh’s bragging rights extend to beyond just altitude, for the new brewery represents another worldly feat the 63-year-old company has accomplished – crafting bespoke vats of soy sauce.

While it’s not uncommon to see the affluent splurge thousands of dollars to procure an exceedingly rare bottle of whisky, it might be difficult to imagine them doing the same for something as seemingly quotidian as soy sauce.

But the fact of the matter is that Koh already has a list full of people willing to shell out at least $10,000 for a vat of tailor-made sauce.

The move to open a brewery in Bhutan, says Koh, is a natural extension of the business which has for years been using Himalayan salt to craft its soy sauce. Besides providing easier access to the salt, the brewery will also be able to utilise the pristine glacier waters which would elevate the quality of the product.

“If we want to bring soy sauce to the next level, this is the place where we could achieve that,” says Koh.

Liquid art

While most people would think of soy sauce as a condiment commonly used in Chinese cooking, Koh points out that such a label does no justice to the storied past of this glistening dark liquid.

“In ancient China, vats of soy sauce used to be passed down from generation to generation as heirlooms. The older the sauce was, the better it tasted,” he says.

“Soy sauce used to be something that was meant to be experienced. But it has become just another commodity today because of the nature of our food supply chain and the need to make things cheap and affordable for the masses.

“But Nanyang Sauce is not catered to the mass market. We will never be.”

Considering that most soy sauces sold in supermarkets cost only a few dollars, the creations by Nanyang Sauce can certainly be considered to be in the luxury range. The cheapest soy sauce by brand costs $12. The more premium Virgin Brew Dark Soya Sauce that has been aged for a year costs S$28.

But this price differential stems not from the desire to be seen as an upmarket brand. Instead, it is largely due to the fact that all soy sauce at Nanyang Sauce is produced using the traditional and labour-intensive process of fermenting soy beans – for nine months. According to Koh, the family business is the only soy sauce brewery in Singapore that still performs each step of the production process manually. Even the bottling and labelling is done by hand.

In contrast, the mass-produced options are often made using chemical hydrolysis. Some brands do not even use soy beans but acid-hydrolysed soy protein instead.

Making soy sauce, Koh ruminates, is akin to creating art. And just like art, no two sauces will taste the same.

“During our appreciation workshops, I would tell participants that even if they’re given the same ingredients, their sauces would taste different after nine months. This is because everyone nurtures his or her own sauce differently,” he says.

“Creating soy sauce is not like a chemical equation where A plus B equals C. It’s not a science. It’s an art form.”

Honouring tradition

-

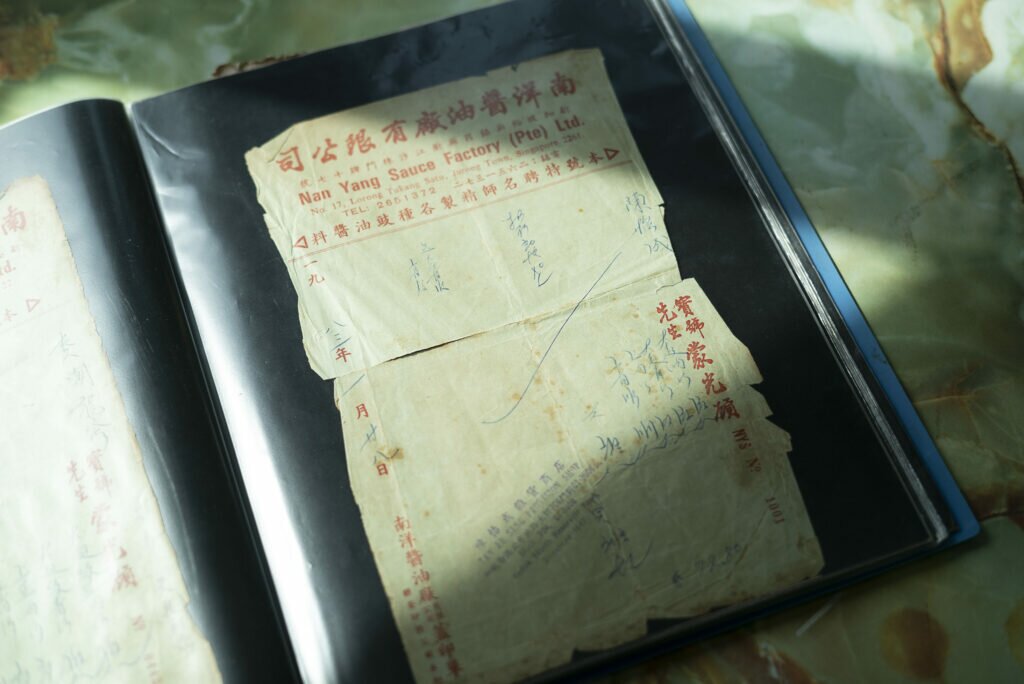

Artefacts from Nanyang Sauce’s museum. -

A decades-old order sheet.

Born into a family of soy sauce makers, Koh spent much of his childhood running around the Golden Swan sauce factory his maternal grandfather Tan Tiong How founded in 1959. Besides helping to pack the product and playing hide-and-seek with his brother amongst the gigantic vats of sauce, Koh also got to see his grandfather manage the business with a panache that left him in awe.

Koh still recalls the day his grandfather berated a group of consultants who were attempting to sell him technology for creating hydrolysed soy sauce.

“He pointed at me and yelled to these men: ‘If I don’t dare to make such a soy sauce for my grandson, how can I feed the rest of Singapore?’ It was only when I got older that I realised the poignance of his actions. To reject a quicker, more profitable way of doing business and sticking with his principles – that required immense courage,” says Koh.

Inspired by his grandfather, Koh developed an entrepreneurial streak that saw him become his own boss when he was in his early twenties. Together with two other alumni from Singapore Management University, Koh started Talentpreneur, a startup that provided training, mentoring and funding for young entrepreneurs, in 2005.

Though that company was performing well, his desire to take over the family business never waned. In fact, seeing how the business had been flailing since the late 1990s – when the emergence of hypermarts resulted in stiffer competition – only strengthened his resolve. The advent of e-commerce in the 2000s exacerbated the situation. But his family had consistently discouraged him from joining what they described as a “sunset industry”.

In 2017, with the company on its last legs, the family decided to sell the business, but the buyout was scuppered at the eleventh hour when the landowners vetoed the deal. Koh saw this as a sign from the heavens.

For the umpteenth time, he tried convincing his parents to hand him the reins.

This time, they relented.

Balancing tradition and modern sensibilities

-

The company’s range of products. -

A limited-edition gift set created by Nanyang Sauce.

One of the first things Koh did after assuming the helm was to determine why profits were dwindling. This led him to soy sauce-producing countries such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Taiwan and Japan. He finally found the answer during one trip to China.

While touring the museum segment of the factory of a major soy sauce producer, Koh stumbled across exhibits depicting the traditional process of sauce making, and it was at this moment that his hairs stood on end.

“That was the aha moment for me,” he says. “That was when I realised that if we can’t be the biggest, the fastest or the most profitable, we could instead be the slowest, the healthiest and the best-tasting.”

“We had to be the most premium soy sauce around.”

To change perceptions of the brand, Koh’s first major undertaking was to set up a boutique selling the newly branded Nanyang Sauce that cost several times more than regular soy sauces. He then organised sauce appreciation classes to raise awareness about the craft and opened a stall selling chicken rice made using Nanyang Sauce.

To reject a quicker, more profitable way of doing business and sticking with his principles – that required immense courage.

Ken Koh

When the brand’s profile grew, business opportunities quickly came knocking. In 2018, the Six Senses hotel group approached Nanyang Sauce to enquire about the creation of gift sets comprising different sauces. The next year, Resorts World Sentosa made a similar request. Today, the company’s gift sets are their second largest source of revenue after regular retail sales.

Koh concedes that his latest endeavour of providing a bespoke soy sauce service came by chance rather than the fecundity of his imagination. He recalls that it was a few years ago when he first received a request from a local businessman to produce soy sauce with a customised flavour profile, bottle and logo.

“My answer to him was no. I said it was too much trouble,” laughs Koh.

In 2020, when another similar request was mooted by a longtime supporter of the brand, Koh conducted market research and solicited feedback from his customers – leading him to realise that there is indeed a market, albeit a niche one, for bespoke sauces.

In February 2021, Nanyang Sauce started fermenting its first batch of bespoke sauce. Deliveries started in December.

Good things are worth the wait

Despite the brand’s growing success, Koh admits that he is still fairly insouciant about the numbers involved in the business. For instance, he’s not entirely sure how much soy sauce he sells each year.

“I just don’t keep track of the numbers. I know it’s not the usual way to run a business,” he says.

“Potential venture capitalists have asked such a question before because they were looking for ways to scale production. But scaling to me is not a priority right now.”

This disposition, he points out, is an about turn from the one he used to have when he was running a startup.

“I think I’ve become more introspective since taking over the family business. Now, I’m all about mindfulness. I like talking about how making sauce is a form of cultivation – what you devote to the cause is what you get. What’s my philosophy in life? That the good things in life are worth waiting for,” he says.

But his apprehension toward scaling the business is by no means a sign that the flourishing brewery is resting on its laurels. Looking ahead, Koh plans to learn more about fermented foods and share with more people the beauty of this process he calls a blessing from Mother Nature. The brand might launch new products in the future, he hinted.

“I want to learn more about not just my industry but also about other things like oyster sauce. I think that being able to appreciate these other sauces better would allow me to better communicate their beauty to my customers and keep traditional heritages alive.”