On 19 June this year, 21-year-old content creator Erick Louis posted a video of himself on his TikTok account (@theericklouis) gearing up to dance to Thot Sh*t, Megan Thee Stallion’s brash new single. “Made a dance to this song!” exclaimed his caption. And usually, such a video — set to a track so snappy and sassy that it invites choreography — is likely to spark off one of those viral dance trends that TikTok is famed for. But, no: after bouncing on his toes a bunch, Louis stops and serves up two middle fingers with the kiss-off, “Sike. This app would be nothing without bl[ac]k people.”

Louis’ post triggered zero dance challenges and instead activated TikTok’s first collective action, #BlackTikTokStrike. From mid-June, black creators ceased creating content on the platform — specifically, they refused to dance to Thot Sh*t — protesting how non-black TikTokers have long co-opted and profited off black creations with nary a line of credit or compensation. As Louis told Vox: “We’re mobilising in this way because it’s necessary and it’s something we’ve been saying among ourselves for quite a while now.”

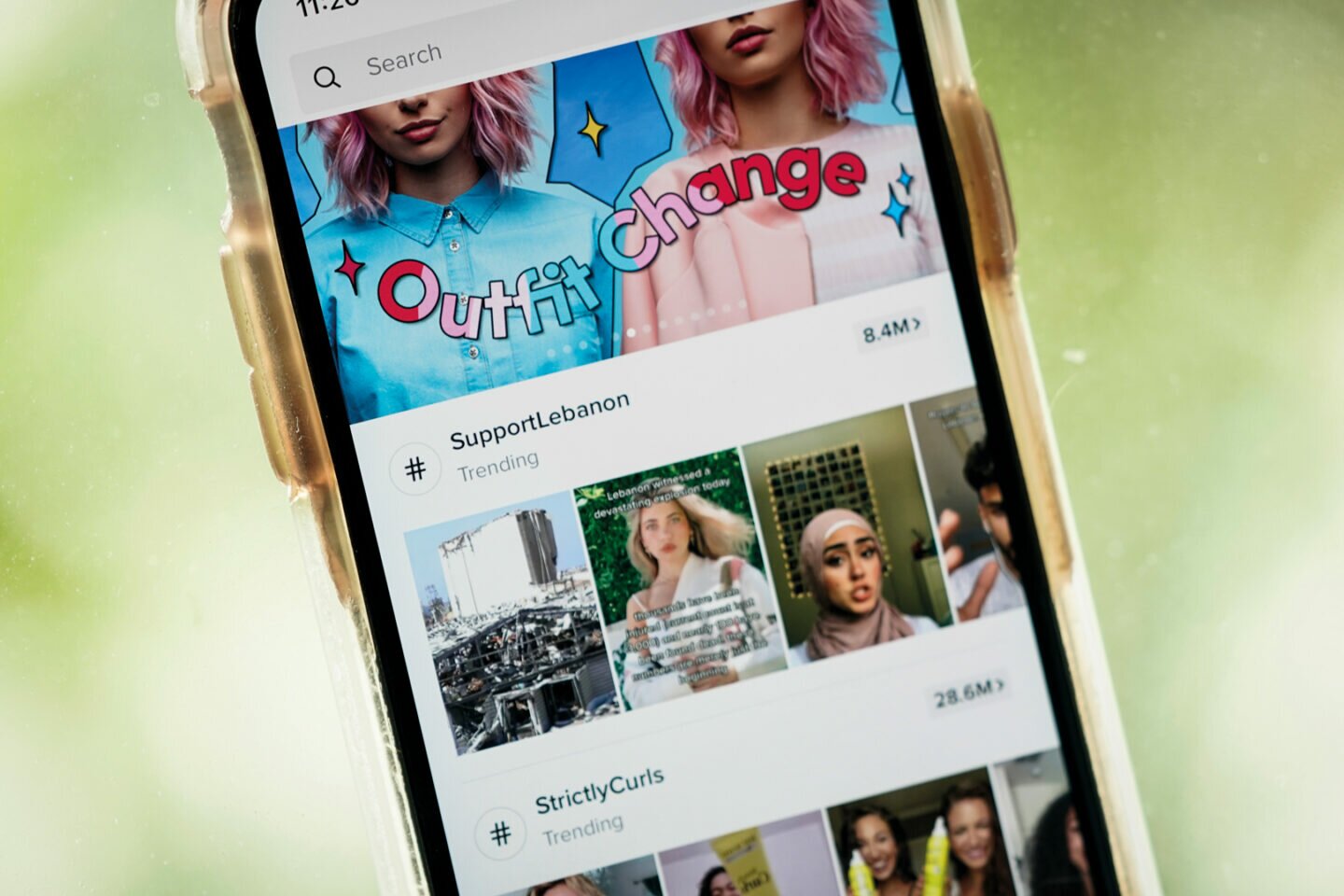

#BlackTikTokStrike had its impact on-app, where Thot Sh*t has yet to spawn a viral dance that’s not inane or tepid, and in the real world, getting picked up by major news outlets from Huffington Post to The New York Times. It’s an effect that bespeaks the force of a joint movement, but also, the cultural potency of TikTok.

The mobile app — which allows users to post videos ranging in length from 15 seconds and up to 3 minutes — remains the world’s fastest growing platform. As of January, TikTok has a reported 689 million active users monthly, easily trumping Snapchat, which hinges on a somewhat similar format; and its global downloads hit three billion in July.

And just who are these users? Quite simply, the young. As per App Ape, in a March 2021 count, a quarter of the platform’s users are teenagers, followed closely by 20-somethings. In fact, at this point, TikTok has become inextricably linked to Gen Z-ers. It’s on the platform where you can find them dressing up, downing kombucha, preening, pranking, confessing to crushes, performing comedic bits, and yes, dancing while lip-syncing.

Oh, and the other thing they’re doing: social activism.

Louis’ demonstration is just one example of how TikTok has become fertile ground for social advocacy, if not a catalyst for social awareness. As of this writing, #DisabilityPride, #EcoFriendly and #MentalHealthAction are trending in the millions while individual TikTokers are spotlighting the lived experiences of their (often underseen) communities. From trans youth like @yazdemand and @jadenspencr to disability activists like @imtiffanyyu to the climate champions on @eco_tok, the platform has no lack of motivated post-millennials endeavoring to reshape the political, cultural and social discourse.

And they’ve come to the right place. TikTok is home to a captive young audience, and its unique algorithm means anyone, at any minute, could go viral. Bonus: that reach is tied to some deep engagement. According to a 2018 survey by Global Web Index, more than half of the TikTokers surveyed either watched, liked, commented or uploaded a video. That’s markedly more than the participation you would find on Facebook or Instagram, where most users are more prone to lurking than liking. Better yet, according to Gem Nwanne (@urdoingreat), TikTokers are a pretty receptive bunch.

“Conversations are difficult to have on Twitter or Instagram because of how reactive everybody is on those apps,” Nwanne told Vox, but over on TikTok, “the community’s a lot chiller, and I do think it’s because they’re younger, so they don’t know how to be pretentious douchebags yet.”

For creators, too, the platform’s short-video format is a boon, inviting a wide range of creativity and expression, and making it ripe for educational messaging via dances, arch captions and crafty storytelling. Case in point: 18-year-old Feroza Aziz’s (@ferozaaziz) unparalleled viral video from November 2019, which purports to be a tutorial on “how to get longer lashes” but neatly segues into a lesson on China’s mass internment of its Muslim population. As Carissa Cabrera (@carissaandclimate), whose 10 March video of a massive flood in her hometown in Oahu, Hawaii, hit upwards of 300,000 likes, told Deutsche Welle: “TikTok is not really a social media app; it can be a learning resource. Gen Z wants the tools and resources, and they want it in a fun way.”

But does all that translate in real life? You bet. Last June, a number of TikTok users (and K-pop fans on Twitter) urged their followers to register for free tickets to then-US President Trump’s rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and simply not show. The result: More than a million ticket requests poured in but fewer than 6,200 actually turned up to fill the 19,000-capacity venue, hitting Trump where it truly hurts: his crowd size. New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez went in for the rub: “You just got ROCKED by teens on TikTok,” she tweeted to the Trump campaign. “Shout out to Zoomers. Y’all make me so proud.”

Reality check, though: TikTok is still a privately owned social media company with attendant social media problems. Privacy is one, censorship is another. Early last year, the platform was accused of blocking the hashtags #GeorgeFloyd and #BlackLivesMatter, which it attributed to a technical bug. Sure. But for black creators in particular, this was a deep-rooted issue, as a tweet, in response to TikTok’s explanation, called out: “We’ve seen the stuff you promote and the stuff you remove from your platform. You are anti-black.”

Not wrong. The app has long been denounced for prioritising the content of white creators over creators of colour, and worse still, censoring these denouncements.

“I made a video about some of the discrepancies between POC creators and white creators,” Marcel Williams (@marcelllei) told CNBC, “and my video was flagged for hate speech.” Aziz, too, had her account locked following her series of clips about the Uighurs in Xinjiang (TikTok’s parent company is the Chinese Bytedance).

So no, TikTok is not a utopia where equity or liberal values flourish — for every EcoTok video, there’s one titled “Hitler Gang”; for all of the company’s propaganda about diversity, there are TikTokers left feeling creatively exploited. Change, on the platform as in reality, remains hard fought, so it’s only fitting that the kids are taking the wheel here to build the kind of world they want to live in.

A TikTok video goes a long way, or as influencer Hana Martin (@hannamartinx) summed it up to the BBC: “Younger people will listen to younger people.”

Take Gillian Sullivan (@gill.no.chill). Back in 2019, the then-16-year-old posted a video of herself expressing deep frustration about the meagre pay of teachers in Nevada’s Clark County School District, who’d been denied raises for years (her mother was one such educator), and calling for a student walkout in solidarity with their teachers. “I’m done and you should be too,” she vented.

She wasn’t alone. Her video went viral, chalking up some 36,000 likes; and before the strike even went ahead, the teachers received their much-deserved pay hikes. Engagement on TikTok, after all, means more than a like count.

“I think my generation realises that we have a voice,” Sullivan told The Cut: “And none of us are really afraid to use it.”